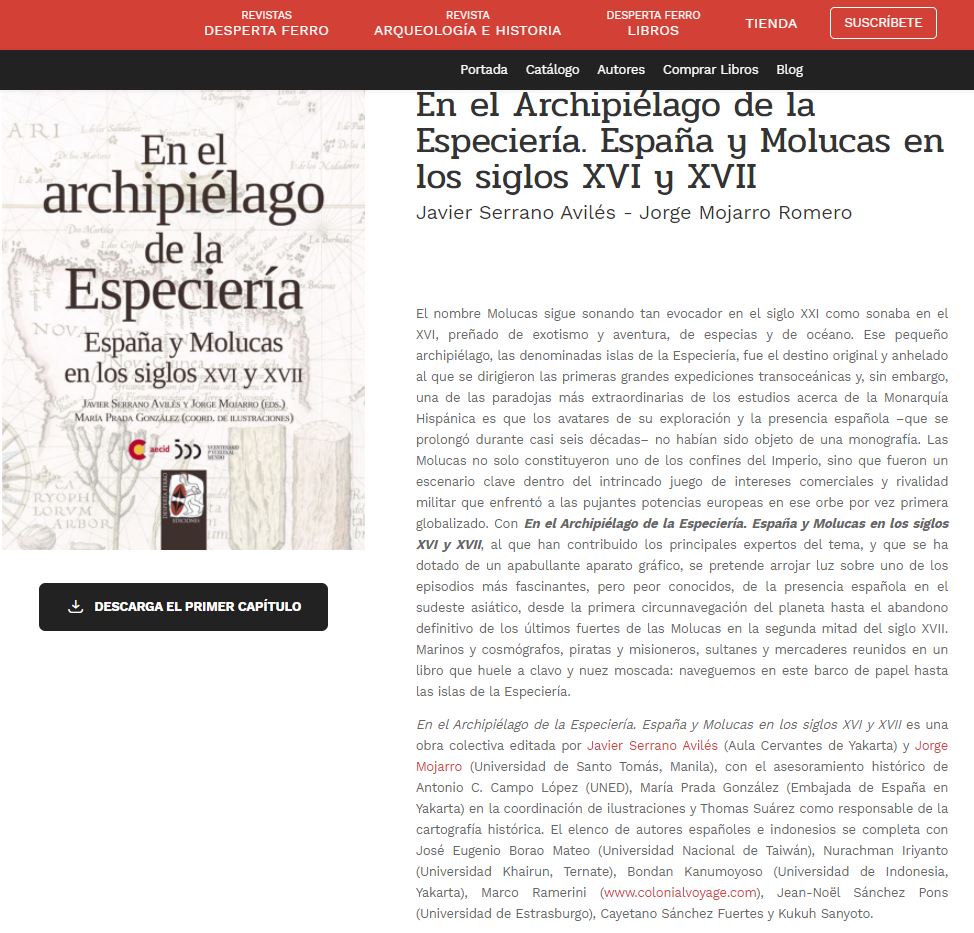

The Spaniards in the Moluccas: 1606-1663/1671-1677. The history of the Spanish presence in the spice islands

Written by Marco Ramerini. 2005-2020/23

INDEX

1: The first contacts of the Spaniards with the Moluccas

2: The conquest of Ternate

3: The government of Juan de Esquivel, May 1606-March 1609

4: The government of Lucas de Vergara Gabiria (acting the functions), March 1609-February 1610

5: The government of Cristóbal de Azcueta Menchaca (who performs the duties), February 1610-March 1612

6: The government of D. Jerónimo de Silva, March 1612-April 1617

7: The government of Lucas de Vergara (Bergara) Gabiria (second term), April 1617-February 1620

8: The government of D. Luis de Bracamonte (who performs the functions), February 1620-1623

9: The government of Pedro de Heredia, 1623-1636

10: The government of D. Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola (who performs the functions), March (?) 1636-January 1640

11: The last Spanish governors of the Moluccas

12: Bibliography

BIBLIOGRAPHY:

UNPUBLISHED DOCUMENTS:

Archivo General de Indias, Seville. AGI:

– “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a Filipinas. Carta de Juan de Esquivel, maese de campo, al Rey, avisándole de su llegada a Filipinas con gente y otras prevenciones para ir a la conquista de Terrenate. Manila, 06-07-1605” Patronato,47,R.1

– “Capitulaciones con el rey de Terrenate. Copia de los puntos que componen las capitulaciones que se hicieron con el rey de Terrenate. Acompaña: Relación de las personas que se prendieron en Terrenate y llevaron a Manila. Terrenate, 1606” Patronato,47,R.11

– “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey llegada a islas Molucas. Carta de Juan de Esquivel, maese de campo, al Rey, avisándole de su llegada y viaje a las islas Molucas. Terrenate, 09-04-1606” Patronato,47,R.2

– “Carta de Ruy Pereira Sangage al Rey de España. 1) Carta de Ruy Pereira Sangage al Rey de España, dándole gracias por la concesión de un pueblo que se le dio en la conquista de Terrenate, en atención a sus servicios. Terrenate, 2 de mayo de 1606. 2) Parecer de don Pedro de Acuña sobre la conducta y persona de Ruy Pereira Sangage. Terrenate, 02-05-1606” Patronato,47,R.16

– “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey progresos islas del Maluco. Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey, participándole los progresos conseguidos en las islas del Maluco desde que las puso a su cargo don Pedro de Acuña. Terrenate, 31-03-1607” Patronato,47,R.22

– “Carta de la Audiencia enviando la de Juan de Esquivel. Carta de la Audiencia de Manila: [Cristóbal] Téllez Almazán, Andrés de Alcaraz, Juan Manuel de la Vega, informando que mandan unos pliegos de Juan de Esquivel, maestre de campo, que había traído un fraile franciscano llegado de Terrenate (V. N.2) y petición de socorros al virrey de México. (Cat. 7446). Manila, 23-07-1607” Filipinas,20,R.1,N.12

– “Carta de Francisco de Uribe al Rey escasez ropas, socorros. Carta de Francisco de Uribe al Rey, avisándole de lo que está sucediendo en el Maluco con motivo de la escasez que tienen de ropas y socorros; trata también del estado en que se hallaba el presidio de Terrenate. Terrenate, 15-05-1608” Patronato,47,R.33

– “Carta del rey de Tidore a Rodrigo Vivero sobre el Maluco. Copia de carta del rey de Tidore a Rodrigo de Vivero, gobernador de Filipinas, informándole del estado en que se encuentra el Maluco, y del gran número de holandeses que allí llegan. En portugués. Tidore, 7-07-1608” Filipinas,7,R.3,N.36

– “Carta de Rodrigo de Vivero al Rey conquista de Maquén. Copia de un capítulo de carta de don Rodrigo de Vivero, escrita el 25 de agosto de 1608 a Su Majestad, en la que dice que el maese de campo Esquivel le avisa de que los holandeses se han apoderado de la isla de Maquén, la más rica del Maluco y que se necesita enviar una armada contra ellos. 25-08-1608” Patronato,47,R.27

– “Carta de Vivero sobre socorro a Juarez Gallinato. Carta de Rodrigo de Vivero, gobernador de Filipinas, diciendo que tras la pérdida de la isla de Maquien en manos holandesas, y ante el péligro que corre Terrenate ha decidido enviar un socorro al capitán Juan Júarez Gallinato, dejando lo de Mindanao para el año que viene. (Cat. 7859). Cavite, 25-08-1608” Filipinas,7,R.3,N.41

– “Carta de Juan de Silva sobre los holandeses y el Maluco. Carta de Juan de Silva, gobernador de las Filipinas, dando cuenta de cómo los holandeses son dueños de todo el Maluco y de la expedición que preparaba contra ellos. (Cat. 8377). Cavite, 05-09-1610” Filipinas,20,R.4,N.38

– “Informaciones: Lucas de Vergara Gaviria. Informaciones de oficio y parte: Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, maestre de Campo y gobernador de las fuerzas de Terrenate. Información con parecer. Manila, 1611” Filipinas,60,N.12

Testimonials of: Fra Rroque de Barrio Nuebo, Fra Antonio Flores, Juan Tomas Maldina o Maldonado, F. (?) de Torralua, Don Fernando de Becerra, Baltasar de Ega ?.

– “Cartas del Virrey Luis de Velasco (El Hijo) (1607-1611). El Virrey a S.M., despachos para Filipinas y Japón. Descubrimiento de islas ricas. Provisión de oficiales en naos de Filipinas. Relación de lo del Maluco. Navío que se compró en el Japón. Castigo de indios alzados en Nueva Vizcaya. Despacho de la hacienda. Mexico, 18-03-1611” Mexico,28,N.13

– “Carta de Jerónimo de Silva a Juan Ruiz de Contreras. Carta de don Jerónimo de Silva a Juan Ruiz de Contreras, avisándole de su llegada a Terrenate, y de la fuerza que tenía el enemigo en aquellos mares e islas. Terrenate, 08-04-1612” Patronato,47,R.35

– “Carta del rey de Tidore al Rey de España. Carta del rey de Tidore al Rey de España, por mano del padre fray Cristóbal de la Concepción, franciscano, suplicando se le conteste a través del padre sobre el estado en que se hallaba aquel país. Tidore 20-04-1612” Patronato,47,R.36

– “Parecer de la Audiencia sobre Pedro de Heredia. Parecer de la Audiencia de Manila: Juan de Silva, [Cristóbal] Téllez Almazán, Andrés de Alcaraz, Manuel de Madrid y Luna, Juan Manuel de La Vega y Juan de Alvarado Bracamonte, recomendando al almirante Pedro de Heredia para la plaza de sargento mayor del real campo de Manila o de general de las galeras, con salario competente. (Cat. 8792). Manila, 20-07-1612” Filipinas,20,R.6,N.50

– “Carta de Silva sobre mala situación en Terrenate. Carta de Juan de Silva, gobernador de Filipinas, dando cuenta del mal estado en que se encuentran las cosas de Terrenate, pide se le envíe una escuadra de navíos que se una a las que allí se puedan disponer. (Cat. 9230). Manila, 19-07-1614” Filipinas,7,R.4,N.51

– “Parecer de la Audiencia sobre Esteban de Alcazar. Parecer de la Audiencia de Manila: Andrés de Alcaraz y Juan Manuel de la Vega recomendando a Esteban de Alcázar, capitán y sargento mayor, como maestre de campo con 3.000 pesos de tributos vacos o que fueren vacando. Esta recomendación no fue firmada por el presidente porque ya había recomendado para esa plaza a otra persona. Con duplicado. (Cat. 9395) Acompaña: Carta de Juan de Silva, gobernador de Filipinas, en contra de la recomendación dada por la Audiencia a Esteban de Alcázar por falta de méritos. Manila, 5 de agosto de 1615. Con duplicado (Cat. 9393). Manila, 07-08-1615” Filipinas,20,R.9,N.57

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Hagonoy, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Hagonoy y Calumpit a Esteban de Alcazar. Resuelto. [f] 21-10-1616” Filipinas,47,N.5

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Meycauayan. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Meycauayan a Fernando de Ayala. Resuelto. [f] 03-03-1617” Filipinas,47,N.7

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Araut. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas del río de Araut, Dumangas, Danepe y Lacayan en la provincia de Pintados (Visayas) en la isla de Panay a Lucas de Vergara Gaviria. Resuelto. Manila, 25-06-1618” Filipinas,47,N.9

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bongol, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bongol, Tanjay y Sipalay en Pintados (Visayas) a Juan de Espinosa y Zayas. Resuelto. [f] 10-10-1618” Filipinas,47,N.11

– “Capítulo de carta de Tenza sobre plazas superfluas. Copia de capítulo de carta de Alonso Fajardo de Tenza, gobernador de Filipinas, sobre la necesidad de refomar las plazas superfluas que habían en esas islas y en Terrenate. Acompaña: Relación de las plazas superfluas existentes en las islas Filipinas y en las de Terrenate. Manila 19-12-1618” Filipinas,20,R.12,N.81

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Balangiga. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Balangiga en Ibabao (Samar) a Gabriel de Coronilla. Resuelto, [f] 27-05-1619” Filipinas,47,N.23

– “Carta de Lucas de Vergara Gaviria al Rey defensa Maluco. Carta de Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, gobernador de Terrenate al Rey, diciéndole que se le ha muerto mucha gente de estas guarniciones, y que por no socorrerle el gobernador de Filipinas, pide auxilio y fuerzas para poder arrojar de allí a los enemigos. Terrenate, 31-05-1619” Patronato,47,R.37

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Laglag, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Laglag y Sibucao en el río Araut y las del estero de Maquila en Cagayan a Pedro de Hermua. Resuelto. [f] 13-07-1619” Filipinas,47,N.28

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Albay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Albay y Canaman en Camarines y Catanduanes, a Gregorio de Vidaña. Resuelto, [f] 21-10-1620” Filipinas,47,N.38

– “Méritos y servicios: Fernando de Ayala:Filipinas. Información de los méritos y servicios del general don Fernando de Ayala. Pasó a las islas Filipinas en 1620 con un navío que se envió desde Nueva España; también obtuvo y desempeñó muchos cargos y comisiones, se halló en la conquista de Terrenate e Ilolo. Manila, 23 de julio de 1622. [c] 23-07-1622” Patronato,53,R.25

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Cuyo. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Cuyo en Calamianes a Juan Martínez de Liedena. Resuelto. [f] 10-02-1623” Filipinas,47,N.47

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Sorsogon en Ibalon (Albay) a Diego de Cabra. Resuelto. [f] 03-07-1623” Filipinas,47,N.53

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Albay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Albay, Taytay, Tiui y Poro a Antonio Gómez. Resuelto. [f] 05-07-1623” Filipinas,47,N.54

– “Meritos Esteban de Alcázar. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Esteban de Alcázar, capitán de infantería, alcaide del Parian de los sangleyes, almirante de las naos de Filipinas. [c] 19-07-1623 (SUP)” Indiferente,161,N.81

– “Meritos: Fernando Centeno Maldonado. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Fernando Centeno Maldonado, general en las Islas Molucas y Filipinas. Manila, 15-08-1623” Indiferente,111,N.43

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Marinduque. Expediente de confirmación de encomienda de la isla de Marinduque a Juan de la Umbria. Resuelto. [f] 02-10-1623” Filipinas,47,N.60

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Tulaque, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Tulaque, Fotol y río de Mandayat en Nueva Segovia a Gabriel de Carranza. Resuelto. [f] 23-10-1623” Filipinas,47,N.62

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Calasiao, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Calasiao y Manabas en Pangasinan a Alonso Martín Quirante. Resuelto. 08-11-1623” Filipinas,47,N.63

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Masbate. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de la isla de Masbate en Ibalon (Albay) a Fernando [Hernando] Suárez. Resuelto. [f] 22-11-1623” Filipinas,47,N.65

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Canaman, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Canaman, Milavit, Camalingan, Bagtas y Daet en Camarines a Pedro Martínez Cid. Resuelto, [f] 23-12-1624” Filipinas,47,N.72

– “Meritos, Juan de Acevedo. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Juan de Acevedo, almirante, sirvió en las Molucas e islas Filipinas. [c] 1625 (SUP)” Indiferente,111,N.56

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Filipinas. Expediente de confirmación de encomienda en el distrito de la Audiencia de Filipinas a Juan Gutierrez Paramo. Resuelto. 10-03-1625” Filipinas,48,N.1

– “Carta de Niño de Távora sobre liberar a rey de Terrenate. Carta de Juan Niño de Távora, gobernador de Filipinas, sobre la necesidad de poner en libertad al rey de Terrenate para la pacificación de esas tierras, a petición de Pedro de Heredia. (Cat. 13361). Manila 30-10-1626” Filipinas,20,R.20,N.151

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Burauen. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Burauen a Bartolomé Díaz Barrera. Resuelto. [f] 18-01-1627” Filipinas,48,N.13

– “Meritos Pedro de Heredia. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Pedro de Heredia, alcayde y Gobernador de la gente de guerra de Terrenate. Manila 22-09-1628” Indiferente,111,N.78

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bislig, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bislig y Catel en Caraga a Francisca de León Escobar. Resuelto, [f] 16-05-1629” Filipinas,48,N.18

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Catubig, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Catubig y Laguan en Ibabao (Samar) a Antonio Menéndez de Valdés. Resuelto. [f] 16-05-1629” Filipinas,48,N.19

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Milavit, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Milavit, Naga y Camalingan en Camarines a Pedro Jaraquemada. Resuelto. [f] 01-08-1629” Filipinas,48,N.24

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Abra, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas del Abra y de Vigan en Ilocos a Juan de la Umbria. Resuelto. [f] 22-11-1629” Filipinas,48,N.28

– “Esteban de Alcázar. Expediente de concesión de licencia para pasar a México a favor de Esteban de Alcázar, capitán y sargento mayor. [f] 1630” Indiferente,2077,N.212

– “Provisión del gobierno de Veragua. Propone personas para el gobierno de Veragua: Juan Hurtado de Mendoza, Juan de Castroverde, Antonio de Figueroa, Lorenzo de Ayala, Jusepe Tello, Lorenzo de la Peña Escalante, Juan García de Navia, Antonio Malaber y Guevara, Juan de Lezama R: “Nombró a don Juan de Castroverde”. [c] 31-05-1630. Madrid” Panama,2,N.5

– “Carta de Niño de Távora sobre Japón, Terrenate, Mindanao. Carta de Juan Niño de Távora, gobernador de Filipinas, dando cuentas del estado del Japón, que tiene armada una flota para atacar las costas de estas islas, y fortificaciones que con esa ocasión se hicieron; socorro a Terrenate; petición del virrey de la India de tres galeones para la flota de la China; sucesos de Nuño Álvarez Botello en Malaca; jornada que se hizo al reino de Joló e isla de Mindanao; reducción de los indios de Cagayán. Manila, 30-07-1630” Filipinas,8,R.1,N.9

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Barugo, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Barugo y Tambo en Cebu a Francisco Jiménez. Resuelto. [f] 18-09-1630” Filipinas,48,N.36

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Sinait, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Sinait y Vigan en Ilocos a Juan García Peláez. Resuelto. [f] 18-09-1630” Filipinas,48,N.37

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Agoo. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Agoo en Pangasinan a Pedro de la Fuente Uriez (sic por Urroz). Resuelto. [f] 28-09-1630” Filipinas,48,N.39

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bondoc. Expediente de confirmación de encomienda de Bondoc en Calilaya a Juan de la Umbria. Resuelto. [f] 02-10-1630” Filipinas,48,N.41

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Candaba, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Candaba y Arayat en Pampanga a Francisco de Vera y Aragón. Resuelto. [f] 09-10-1630” Filipinas,48,N.44

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Baro. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Baro en Ilocos a Hernando Suárez. Resuelto. [f] 02-12-1630” Filipinas,48,N.45

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bacon, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bacon y costa de Bucaygan en la provincia de Camarines, a Martín de Adaro. Resuelto. [f] 01-02-1631” Filipinas,48,N.48

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Caraga. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Caraga a Juan de Chaves. Resuelto. [f] 14-02-1631” Filipinas,48,N.49

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Meycauayan. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Meycauayan en Bulacan a Gonzalo Ronquillo. Resuelto. [f] 31-02-1631 (SIC)” Filipinas,48,N.50

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Palanan de Manila a Francisco Carreño. Resuelto. [f] 07-04-1631” Filipinas,48,N.52

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Binalbagan. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Binalbagan en la isla de Negros a Pedro Martínez. Resuelto. [f] 31-10-1631” Filipinas,48,N.54

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Abuyog, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Abuyog en la isla de Leyte y Potat en la isla de Cebu a Pedro Méndez de Sotomayor. Resuelto. [f] 02-11-1631” Filipinas,48,N.55

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bato, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bato, Lulu, Purao, Culi, Simbuey, Gattaran, Talapa en Cagayan a Juan Muñoz. Resuelto. [f] 12-12-1631” Filipinas,48,N.57

– “Meritos: Diego de Azcueta y Menchaca. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Diego Azcueta y Menchaca, alcalde ordinario de la ciudad de Manila. Referencias: Cristóbal de Azcueta y Menchaca, General en Filipinas. 1632” Indiferente,111,N.134

– “Informaciones: Pedro de la Fuente Urroz. Informaciones de oficio y parte: Pedro de la Fuente Urroz, capitán, vecino de Manila. Informaciones y poder. [f] 1632” Filipinas,61,N.12

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Ayumbon, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Ayumbon y Sanctor en Pampanga a Rodrigo de Mesa. Resuelto. [f] 02-07-1633” Filipinas,48,N.64

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Guisan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Guisan, Lantac, Adpili, Panglao, Masago, Panaon y Ormoc en Cebu en Leyte a Juan de Medina Bermudez. Resuelto. [f] 12-08-1633” Filipinas,48,N.67

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Batan. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Batan en Pampanga a Fernando de Ayala. Resuelto. [f] 05-09-1633” Filipinas,48,N.70

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Barugo, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Barugo y Tambo en Leyte a Francisco Jiménez. Resuelto. [f] 07-09-1633” Filipinas,48,N.71

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Maquila, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Maquila y Tulaque en Cagayan a Agustín Pérez. Resuelto. [f] 21-10-1633” Filipinas,48,N.76

– “Meritos: Lorenzo Bravo de Cuellar. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Lorenzo Bravo de Cuéllar, que sirvió en las islas Filipinas. [c] 10-01-1634” Indiferente,111,N.152

– “Carta de Corcuera sobre socorro de Terrenate y Cachil Naro. Carta de Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, gobernador de Filipinas, dando cuenta del envío del socorro a Terrenate; encuentro que tuvieron con un galeón enemigo y regreso del gobernador de Terrenate, Pedro de Heredia. Por triplicado. (Cat. 16196) Acompaña: Orden e instrucción que los generales Pedro [Muñoz de Carmona y] Mendiola, gobernador de Terrenate y Jerónimo Somonte, capitán general de la armada real deben de guardar en razón de la restitución del rey Cachil Naro a su reino. Manila, 5 de julio de 1636. Con duplicado. (Cat. 16199). [c] 02-07-1636. Manila” Filipinas,8,R.3,N.72

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Santa Catalina. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Santa Catalina a Alonso Serrano. Resuelto. [f] 19-09-1638” Filipinas,49,N.25

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Tulaque, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Tulaque, Mandayat y Buguey en Cagayan a Pedro de Mora. Resuelto, [f] 13-05-1639” Filipinas,49,N.31

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Meycauayan. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Meycauayan en Bulacan a Jerónimo Somonte. Resuelto. [f] 13-05-1639” Filipinas,49,N.32

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Pata, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Pata y Masi en Cagayan a Francisco Suarez de Figueroa. Resuelto, [f] 19-08-1639” Filipinas,49,N.38

– “Informaciones: Pedro Jaraquemada. Informaciones de oficio y parte: Pedro Jaraquemada, capitán y sargento mayor, vecino de Manila. [f] 1640” Filipinas,61,N.19

– “Meritos: Fernando de Ayala. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Fernando de Ayala, castellano interino de Manila y maestre de campo. [c] 27-07-1643” Indiferente,112,N.47

– “Meritos: Hernando del Castillo. Relación de Méritos y servicios del capitán Hernando del Castillo, vecino de Manila. [c] 1645 (SUP)” Indiferente,112,N.145

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Viri. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Viri en Ibabao (Samar) a Ginés Rojas Narvaez. Resuelto. [f] 09-01-1645” Filipinas,49,N.61

– “Meritos: Diego Sarria y Lazcano. Relación de Méritos y servicios del almirante Diego Sarria y Lazcano, residente en las islas Filipinas. 01-1647” Indiferente,113,N.37

– “Meritos: Pedro Fernández del Rio. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Pedro Fernández del Rio, Gobernador de la gente de guerra de Terrenate. [c] 05-1647” Indiferente,113,N.50

– “Meritos: Francisco del Castillo Relación de Méritos y servicios del capitán Francisco del Castillo, residente en Filipinas, alcalde mayor de Balayan. [c] 20-05-1647” Indiferente,113,N.48

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bacnotan, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bacnotan y Binmaley en Pangasinan a Pedro Muñoz de [Carmona y] Mendiola. Resuelto. [f] 23-05-1647” FILIPINAS,49,N.66

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Dalaguete, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Dalaguete y Panglao en la provincia de Cebu a Francisco de Atienza Ibáñez. Resuelto. [f] 06-06-1647” Filipinas,49,N.68

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Antique. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Antique en Oton a Juan de Heredia Ormastegui. Resuelto. [f] 13-09-1647” Filipinas,49,N.69

– “Meritos: Jerónimo Somonte. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Jerónimo Somonte, General en Filipinas. Referencias: José de Somonte Juan de Somonte Observaciones: Ampliada hasta 12-1655. [c] 02-05-1648” Indiferente,116,N.2

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Tulaque. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Tulaque en Cagayan a Lope de Colindres. Resuelto. [f] 24-04-1649” Filipinas,50,N.2

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Sequior, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Sequior en Cebu, Ilaguan en Leyte y Borongan a Juan Fernandez Sevillano. Resuelto. [f] 02-05-1649” Filipinas,50,N.6

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Majayjay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Majayjay y Santa Cruz en La Laguna de Bay a Pedro de Almonte y Verastegui. Resuelto. [f] 02-05-1649” Filipinas,50,N.7

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Santa Catalina,etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Santa Catalina en Ilocos y Dumaguete y Tanjay en la isla de Negros a Rafael Home de Acevedo. Resuelto. [f] 18-05-1649” Filipinas,50,N.10

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Candaba, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Candaba, Arayat, Cagalissan, Bani y Apalit en Pampanga a Marcos Zapata de Carvajal. Resuelto. [f] 04-09-1649” Filipinas,50,N.12

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Sampongan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Sampongan, Anbongal, Maylon, El Buqui, Iligan, Bayu, Balo, Naguan, Tog, Baganga, Manoliguo, Caragan, Manay, Marayo, Casalman, Quinolan y Bitanagan a Diego Maldonado Bonal. Resuelto. [f] 07-10-1649” Filipinas,50,N.14

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Libmanan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Libmanan en Camarines, Burias y Masbate en Ibalon (Albay), Batan, Maripipi, Liman y Cabayan en Cebu a Francisco de Atienza Ibañez. Resuelto. [f] 16-10-1649” Filipinas,50,N.17

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Narvacan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Narvacan en Ilocos y Tingue de Baon, por otro nombre Danao en Oton a Lorenzo de Orella y Ugalde. Resuelto. [f] 23-10-1649” Filipinas,50,N.18”

Non c’è niente su Ternate

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Buguey. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Buguey en Ibalon (Albay) a Luisa Suárez. Resuelto. [f] 26-11-1649” Filipinas,50,N.19

– “Carta de Diego Fajardo sobre procesos contra los que ayudaban a Corcuera. Carta de Diego Fajardo Chacón, gobernador de Filipinas, dando cuenta del proceso seguido contra los que apoyaban a Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, su antecesor, en la difamación de su gobierno y que acabó con la ejecución de Juan Ramos, alférez, y el destierro a los distintos presidios de estas islas de Lucrecia de Maldonado, Alonso Centeno, sargento mayor, Pedro de Almonte [y Verastegui] general de la armada que iba contra los holandeses, Francisco Rojo, sargento mayor de esta armada, Diego Sarriá, de los capitanes Marcos de Resinas (sic por Rasines), Andrés de Chaves, Laureano de Escobar, Francisco de Sierra, Juan de Salinas, y de los ayudantes Hernán Gómez Grande y Pedro de Garay, todos sus cómplices. (Cat. 18866). [c] 24-01-1650. Manila” Filipinas,9,R.1,N.10

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Guimbal. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Guimbal en Oton a Esteban de Somoza y Losada. Resuelto. [f] 02-02-1651” Filipinas,50,N.20

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Baler. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Baler en Tayabas a Alonso Romero. Resuelto. [f] 04-03-1651” Filipinas,50,N.24

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Guisan. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Guisan, Lantac, Adpili, Panglao, Masago, Panaon y Ormoc en Cebu a Alonso López. Resuelto. [f] 28-04-1651” Filipinas,50,N.29

– “Meritos: Francisco Claudio Arias de Verastegui, Relación de Méritos y servicios de Francisco Claudio Arias de Verastigui, capitán, sirvió en Filipinas. Referencias: Juan Claudio Arias de Verastegui Pedro de Brito Sebastián Pérez de Acuña. Nota: No hay relación. [c] 10-07-1651” Indiferente,114,N.30

– “Meritos: Agustín Cepeda. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Agustín Cepeda, Gobernador de la gente de guerra de la fuerza de san Sebastián en la isla de Mindanao. Observaciones: Ampliada hasta 1667-03-10. [c] 01-07-1652” Indiferente,121,N.89

– “Meritos: Juan Camacho de la Peña. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Juan Camacho de la Peña, sargento mayor en las islas Filipinas. [c] 15-07-1652” Indiferente,114,N.56

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Agoo. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Agoo en Pangasinan a Antonio Pérez. Resuelto. [f] 02-10-1653” Filipinas,50,N.39

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bagatayan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bagatayan, Pajo y Liloan en Cebu, Bislig y Catel en Caraga a Juan Camacho de la Peña. Resuelto. [f] 09-10-1653” Filipinas,50,N.40

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Binalatonga, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Binalatonga, Bolonguey y Telban en Pangansinan a Francisco de Palmas. Resuelto. [f] 22-06-1654” Filipinas,50,N.44

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bito, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bito, Binca, Manliron y Malaguicay en las provincias de Leyte, Samar e Ibabao (Samar) a Francisco de Alfaro. Resuelto. [f] 22-08-1654” Filipinas,50,N.45

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Naujan, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Naujan, Bongabon, Santiago, Lin y Baco en la isla de Mindoro a Juan de Chaves. Resuelto, [f] 25-08-1654” Filipinas,50,N.47

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Tulaque, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Tulaque, Mandayat y Buguey en Cagayan a Julián de Torres. Resuelto. [f] 23-11-1654” Filipinas,50,N.48

– “Meritos: Ginés Rojas y Narvaez. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Ginés Rojas y Narváez, castellano del castillo de Santiago en Manila, [c] 29-11-1655” Indiferente,116,N.42

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Balayan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Balayan y bajos de Tuley a Simón Alvarez. Resuelto. [f] 03-12-1655” Filipinas,50,N.51

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Maquila, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Maquila, Tulaque y Mandayat en Cagayan a Juan de Zabaleta. Resuelto. [f] 09-12-1655” Filipinas,50,N.53

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Binalatonga, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Binalatonga, Bolonguey y Telban en Pangasinan a Miguel de Guinea. Resuelto, [f] 09-12-1655” Filipinas,50,N.52

– “Meritos: Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola, Gobernador de Terrenate. Observaciones: Ampliada hasta 17-12-1657. Manila, 29-12-1655” Indiferente,116,N.48

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Caraga, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Caraga, Surigao y Sidarga en Cebu a Martín Sánchez de la Cuesta. Resuelto. [f] 19-06-1659” Filipinas,51,N.1

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Paracale, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Paracale y Capalonga en Camarines a Antonio Maldonado y Moscoso. Resuelto. [f] 05-07-1659” Filipinas,51,N.3

– “Meritos: Francisco Esteybar. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Francisco Esteybar, General, sirvió en Terrenate y Zamboanga. Manila, 15-07-1659” Indiferente,118,N.24

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Bondoc, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bondoc y Catanauan en Tayabas y Marinduque en Mindoro a Francisco de Arechaga y Bolivar. Resuelto. [f] 19-07-1659” Filipinas,51,N.6

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Binalbagan, etc.Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Binalbagan en isla de Negros, Dumangas y Baon en Oton a Ginés Rojas y Narváez. Resuelto. [f] 17-09-1659” Filipinas,51,N.10

– “Meritos: Andrés Ezquerra. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Andrés Ezquerra, capitán, sirvió en Filipinas. Referencias: Gonzalo Carvajal Andrés Esquerra Francisco Ezquerra Juan Ezquerra Gabriel Rivera Gonzalo Sánchez Carvajal, escudero. [c] 23-10-1659” Indiferente,118,N.44

– “Meritos: Pedro Bravo de Acuña. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Pedro Bravo de Acuña, Capitán, sirvió en Filipinas, Armada, La Habana y San Antonio de Gibraltar. [c] 07-03-1660” Indiferente,118,N.65

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Payo, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Payo en Catanduanes, Tocava y Caraco en la isla de Negros a José Cerrillo. Resuelto. f] 06-04-1661” Filipinas,51,N.11

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Palanan en Tayabas a Manuel Correa. Resuelto. [f] 28-11-1661” Filipinas,51,N.12

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Abucay y Samal en Pampanga a Francisco de Esteybar. Resuelto. [f] 17-12-1661” Filipinas,51,N.14

– “Meritos: Lorenzo Orella y Ugalde. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Lorenzo Orella y Ugalde, castellano de Santiago de Manila. Referencias: Esteban Orella y Ugalde, castellano de Xolo. [c] 19-12-1663” Indiferente,120,N.43

– “Meritos: Lorenzo de Orella y Ugalde. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Lorenzo de Orella y Ugalde, castellano del castillo de Santiago de Manila. [c] 19-12-1663” Indiferente,161,N.334

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Abucay y Samal a Francisco de Esteybar. Resuelto. [f] 24-10-1666” Filipinas,52,N.4

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Aranguen, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Aranguen, Guisan, Buruanga y Simara en Panay a Juan Atienza Ibáñez. Resuelto. [f] 02-12-1666” Filipinas,53,N.6 NON C’è’NIENTE

– “Confirmación de encomienda de San Jacinto, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de San Jacinto y Magaldan en Pangasinan a Francisco Prado de Quirós. Resuelto. [f] 23-12-1666” Filipinas,52,N.14

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Pata, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Pata y Masi en Cagayan a Hernando López del Clavo. Resuelto. [f] 10-11-1667” Filipinas,53,N.9

– “Meritos: Juan de Eguizabal. Relación de Méritos y servicios de Juan de Eguizabal, capitán de infantería. [c] 02-03-1669” Indiferente,122,N.69

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Dumon, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Dumon y Maguin en Cagayan a Miguel Gutiérrez. Resuelto. [f] 02-05-1676” Filipinas,54,N.5

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Palanan en Tayabas a Pedro Lozano. Resuelto. [f] 02-05-1676” Filipinas,54,N.6

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Mambusao. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Mambusao en Panay a Sebastián de Villarreal. Resuelto. [f] 19-05-1676” Filipinas,54,N.11

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Baratao. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Baratao en Pangasinan a Alonso Lozano. Resuelto. [f] 16-06-1676” Filipinas,54,N.12

– “Carta de Juan de Vargas sobre méritos de Marcos Bedoya. Carta de Juan de Vargas Hurtado, gobernador de Filipinas, informando sobre los méritos de Marcos Bedoya. Acompaña: Real decreto remitiendo al Conde de Medellín, [presidente del Consejo de Indias], memorial de Marcos Bedoya. Madrid, 16 de junio de 1678. – Memorial de Marcos de Bedoya pidiendo una encomienda de indios. Manila, 10 de junio de 1677. [c] 05-06-1680” Filipinas,11,R.1,N.15

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Santa Catalina Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Santa Catalina en Ilocos a Alonso del Castillo. Resuelto[f] 17-12-1686” Filipinas,55,N.12

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Siniloan, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Siniloan y Mabitac en La Laguna de Bay a Juan Martínez de Arce. Resuelto. [f] 18-01-1687” Filipinas,55,N.14

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Quinagon. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Quinagon en Leyte a Juan García. Resuelto[f]. 17-04-1692” Filipinas,57,N.7

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Aranguen, etc. Expediente de confirmacion de las encomiendas de Aranguen, Simara, Guisan y Borongan en Panay a Pascual de Aguirre. Resuelto. [f] 06-03-1694” Filipinas,58,N.1

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Casiguran, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Casiguran y Sorsogon, en Ibalon (Albay) y Catanduanes a Alonso de la Serna. Resuelto. [f] 07-06-1695” Filipinas,57,N.15

– “Confirmación de encomienda de Nabua, etc. Expediente de confirmacion de las encomiendas de Nabua, Iriga, Minalabag y Tabuco en Camarines a Juan de las Casas. Resuelto. [f] 15-06-1699” Filipinas,58,N.10

Archivo Franciscano Ibero Oriental, Madrid:

– Fr. Gregorio de San Esteban “Memoria y Relacion e historia verdadera de los sucedido en las Islas Malucas desde el tiempo y governo de D. Juan de Silva ….”

Nationaal Archief, Den Haag. ARA:

– VOC 1056, fols. 87-92 “Message from Jacques Specx written at the conquered Portuguese fort on the island of Tidor, 1613”

– VOC 1056, fols. 119-126 “Message from Lourens Rael at the conquered Portuguese fort on Tidor, 1613”

– VOC 1094, fols. 252-296 “Daily report on the island of Molucca by Jaque le Febre, covering the period from 17-08-1627/31-03-1628”

– VOC 1208, fols. 140-141 “Answer by Jacob Hustaert to the questions asked by Arnold Vlamingh van Oudtshoorn, related to the war with Tidore, 22-06-1654”

– VOC 1211, fols. 904-909 “Message from the Spanish governor in Gammelamme to Governor Jacob Hustaert of Ternate with answer dated 27-02-1655”

– VOC 1229, fols. 742-743 “Conditions of the nine month peace treaty with Spain signed in Ternate, 1660”

– VOC 8076 Ternate, 1707 p. 429-430

– VOC 3677, fols. 192-202 “Secret papers, Resolution of 14 Feb. 1784, Report by Hemmekan on the spedition to Tidore”

PUBLISHED CONTEMPORARY SOURCES:

– AA. VV. “Correspondencia de D. Jeronimo de Silva con Felipe III, D. Juan de Silva, el Rey de Tidore y otros personajes, desde abril 1612 hasta febrero de 1617, sobre el estado de las islas Molucas”

In: “Coleccíon de documentos inéditos para la historia de España” vol. n°52, 1868, Madrid, Spagna. pp. 5-439

Very important collection of documents for the years 1612-1617.

– AA. VV. “The voyage of Sir Henry Middleton to the Moluccas, 1604-1606”

xliii+209 pp. Hakluyt Society, Kraus Reprint, 1990, Millwood, NY, USA.

– AA. VV. “Daghregister gehouden int Casteel Batavia vant passeerende daer ter plaetse als over geheel Nederlandts-India”

1624-1629; 1631-1634; 1659; 1661; 1663; 1664, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

– Anonymous “Relação breve da Ilha de Ternate, Tydore, e mais Ilhas Malucas aonde temos fortaleza e presidios e das forças. Naos e fortalezas, que o enemigo olandês tem por aquellas partes, Malaca 28 novembre 1619”

Manuscript present on folios 41-48 of the codex n.o 3015 “Descripcion de la India Oriental. Govierno de ella y sucesos acaecidos en el ano 1639” Biblioteca Nacional, Madrid.

Published in “Documantação Ultramarina Portuguesa” vol. II pp. 49-56

AA. VV. “Documantação Ultramarina Portuguesa”

8 volumes CEHU, 1960-1962-1963-1966-1967-1973-1975-1983, Lisbon, Portugal.

The same document is also reproduced in “Documantação Ultramarina Portuguesa” vol. I pp. 163-170 where it is reproduced from folios 172-178 of manuscript n°28461 in the British Museum in London.

– Anonymous “Livro das cidades, e fortalezas, que a coroa de Portugal tem nas partes da India, e das capitanias, e mais cargos que nelas ha, e da importancia delles” ca. 1582

CEHU, 1960, Lisbon, Portugal.

– Anonymous “Declaracion de un holandés llamado Juan, que se halló con otros en la factoria de Tidori, sobre los navios en que vino a Maluco, cuántos eran, por mandado de quién vinieron, etc. Tidori, 16 de marzo [1606]”

Manuscript from the Archive of Seville 67-6-19. (fs. 106)

In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 14 (1605-1609), pp. 112-118 under the title “The Dutch factory at Tidore”

– Anonimo “Entrada de la seraphica religion de nuestro P. S. Francisco en las Islas Filipinas”

Manuscript of 1649, published in: Rentana, W. E. “Archivo del bibliófilo filipino” Tomo I Libro III, 57 pp.

– Argensola, B. Leonardo de “Conquista de las islas Malucas al Rey Felipe Tercero”

372 pp. (prima edizione 1609) Miraguano Ediciones & Ediciones Polifemo, 1992, Madrid, España.

– Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898: explorations by early navigators, descriptions of the islands and their peoples, their history and records of the Catholic missions, as related in contemporaneous books and manuscripts, showing the political, economic, commercial and religious conditions of those islands from their earliest relations with European nations to the close of the nineteenth century”

(55 vols. First edition 1903-1909, Cleveland, Ohio, USA) CD-Rom, Bank of the Philippine Islands, Manila, Philippines.

Which publishes in English translation many sources and letters from various archives.

– Bocarro, A. “Decada XIII da historia da India”

805 pp. 2 vols. Academia Real das Sciencias de Lisboa, 1876, Lisbona, Portogallo.

– Booy, A. de “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden”

2 vols. xviii+213/xii+274 pp. Linschoten Vereeniging, 1968-1970, s’Gravenhage, NL.

– Borao Mateo, José Eugenio “Spaniards in Taiwan”

2 volls. lxvi+lxvi+697 pp. SMC Publishing, 2001, Taipei, Taiwan.

– Castanheda, Fernao Lopes de “Historia do descobrimento e conquista da India pelos Portuguêses”

2 volumi, Lello & Irmao, 1979, Porto, Portogallo.

Vol. I, xxxvi+969 pp.

Vol. II, 1035 pp.

– Coen, J. P. “Aanval op Tidore”

In: Colenbrander, H. T. “Jan Pietersz Coen. Bescheiden omtrent zijn bedrijf in Indië”

vol. I, pp. 16-21 where the attack on Tidore on 7 July 1613 is described.

– Colin, Francisco S. I. “Labor Evangelica, ministerios apostolicos de los obreros de la Compania de Jesus, fundacion, y progresos de su provincia en las Islas Filipinas”

Tomo III: 831 pp.

3 volumi (Vol. I: xix+239+636 pp.; Vol. II: 725 pp.; Vol. III: 831 pp.) (prima edizione 1663) Imprenta y Litografía de Henrich y Compañía, 1900-1903, Barcellona, Spagna.

The history of Jesuit missions in the Philippines from their founding to 1616.

Especially interesting are the notes compiled by Fr. Pablo Pastells, S.J., where many unpublished contemporary documents are reproduced.

– Coolhaas, W. Ph. “Generale missiven van Gouverneurs-Generaal en Raden aan Heren 17 der Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie”

7 vols. (1610-1725) 1960-1979, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

Consultati:

Vol. I (1610-1638) xxiv+784 pp. 1960, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

Vol. II (1639-1655) xvi + 872 pp. 1964, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

Vol. III (1655-1674) XIV + 1008 pp. 1968, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

– Correia, Gaspar “Lendas da India”

4 volumi, Lello & Irmao, 1975, Porto, Portogallo.

Vol. I, xxxvi+1013 pp.

Vol. II, 985 pp.

Vol. III, 909 pp.

Vol. IV, 756+106 pp.

– Couto, Diogo do “Da Asia. Dos feitos que os Portuguezes fizeram na conquista e descubrimento das terras e mares do Oriente”

Decadas IV-XII, 14 volumi (volumi 10-24), 1973-1975 (1778-1788), Lisbona, Portogallo.

– Jacobs, H. “Documenta Malucensia I, 1542-1577”

xxxix+84*+758 pp. Jesuit Historical Institute, 1974, Roma, Italia.

– Jacobs, H. “Documenta Malucensia II, 1577-1606”

xxxi+65*+794 pp. Jesuit Historical Institute, 1980, Roma, Italia.

– Jacobs, H. “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682”

xxiii+54*+777 pp. Jesuit Historical Institute, 1984, Roma, Italia.

– Jacobs, H. “A treatise on the Moluccas (c. 1544)”

402 pp. Jesuit Historical Institute, 1971, Roma, Italia.

– Morga, Antonio de “Sucesos de las Islas Filipinas”

(prima edizione 1609) 1997, Madrid, España.

– Opstall, M. E. van “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azië, 1607-1612”

2 vols. xviii + 441 pp. Linschoten Vereeniging, 1972, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

– Pimpín, T. “Sucesos felices que por mar y tierra ha dado N.tro Señor a las armas Españolas en las Islas Filipinas contra el Mindanao y en las de Terrenate, contra los Holandeses por fin del año de 1636 y principio del de 1637”

1637, Manila, Filippine.

Published in: Rentana, W. E. “Archivo del bibliófilo filipino” Tomo IV pp. 113-136

– Prado, Don Diego de “The discovery of Australia”

1608

Translated, annotated and indexed by G. F. Barwick, British Museum, 1922.

Pdf version.

– Prevost, Abate Antonio Francisco “Historia General de los viajes, ó nueva colección de todas las relaciones de los que se han hecho por Mar y Tierra… Tomo XIII: Viajes de los Holandeses a las Indias Orientales”

480 pp. Imprenta de Don Juan Antonio Lozano, 1773, Madrid, Spagna.

– Ramusio, Giovanni Battista “Navigazioni e Viaggi”

6 voll. I Millenni, Giulio Einaudi editore, 1978-88

First electronic edition dated June 3, 1999

– Rietbergen, P. J. A. N. “De eerste landvoogd Pieter Both (1568-1615)”

2 vols. (184) 360 pp. Linschoten Vereeniging n° 86-87, De Walburg Pers, 1987, Zutphen, NL.

– Rios Coronel, Hernando de los “Memorial y relacion para su Magestad del procurador general de las Filipinas, de lo que conviene remediar, y de la riqueza que ay en ellas, y en las Islas del Maluco”

1621, Madrid, Spagna.

In: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 19 (1620-1621), pp. 187-297

– Sá, Artur Basilio de “Documantação para a historia das missoes do padroado português do Oriente. Insulindia” vol. II, IV, V, VI

pp. 432 Instituto de Investigaçao Cientifica Tropical, 1988, Lisbona , Portogallo.

– Schotte, Apollonius “Discours van den seer vermaerden Apolini Schot (Apollonius Schotte)”

Where an account is given of the forces present in the Moluccas in 1612.

In: Warnsinck, J.C.M. (ed.), “De reis om de wereld van Joris van Spilbergen, 1614-1617” 2 vols. cxxxi+(5)+192, Linschoten Vereeniging, n°47, Nijhoff, 1943, ‘s-Grv., NL.

Vol. I pp. 114-128.

– Tiele, P. A. & Heeres, J. E. “Bouwstoffen voor de geschiedenis der Nederlanders in den Maleischen Archipel”

1890 (Vol. II: 1623-1640), 1895 (Vol. III: 1640-1649), s’Gravenhage, NL.

– Trindade, Paulo da “Conquista espiritual do Oriente”

3 volls. xxxi+414; xv+456; xx+606; Centro de Estudos Histórico Ultramarinos,

1962, 1964, 1967, Lisbona, Portugal.

– San Agustín, Gaspar de “Conquistas de las Islas Filipinas (1565-1615)”

lxiv + 789 pp. C.S.I.C. Inst. Enrique Florez, 1975, Madrid, Spagna.

– Varela, C. (Ed., introducciòn y notas de) “El viaje de don Ruy Lopez de Villalobos a las islas del Poniente, 1542-1548”

pp. x+202 Coll.Letterature e Culture dell’America Latina, Cisalpino, 1983, Milano, Italia.

– Verken, Johann “Molukken-Reise, 1607-1612”

pp. 146 (Reisebeschreibungen von Deutschen Beamten und Kriegsleuten im Dienst der Niederländischen Westy-und ost-Indischen Kompagnien, 1602-1797, Band 2), 1930, Haag.

– Yranzo (Iranzo), Juan O. S. F. “Relacion de los sucedido en Manados” c. 1645

Archivo de Pastrana, Provincia de S. Gregorio; caj. 7, leg. 2

Pubblicata in: Pérez, Lorenzo O.F.M. “Historia de las misiones de los Franciscanos en las islas Malucas y Célebes” pp. 636-644

CONTEMPORARY OR ALMOST CONTEMPORARY GRAPHIC REPRESENTATIONS AND MAPS:

– Anonymous “De stad Gammelamme op Ternate” 1599

“Begin ende Voortgangh van de Vereenighde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie”

1646 I, Tweede Schipvaerd, afb. 25, p.33

– Anonymous “T’fort Mariecco op t’eylant Tidore”

Preserved in the French National Library, Paris: “Collezione Gaignieres” 6545”

– Anonymous “Tidor en Mitarra, 2 kleine eil. Ten Z. van Ternate, ten W. van Gilolo op Halmahera”

Preserved in the University Library of Leiden, the Netherlands: “Collectie Bodel Nijenhuis” P. 314-I-n° 99

Interesting representation of the west coast of Tidore, undated but probably executed around 1628.

– Anonymous “T’eylant Ternate”

Preserved in the University Library of Leiden, the Netherlands: “Collectie Bodel Nijenhuis” 002-09-022

Interesting representation of the coast of Ternate, undated but probably executed around 1628.

– Anonymous “Dese 2 forten liggen int eylant Macquian op Tabulolo”

Preserved in the University Library of Leiden, the Netherlands: “Collectie Bodel Nijenhuis” 002-12-028

Interesting representation of the Tabulolo fort on Makian Island, undated but probably executed around 1628.

– Anonymous “T’fort Tafasoha”

Preserved in the University Library of Leiden, the Netherlands: “Collectie Bodel Nijenhuis” 002-12-027

Interesting representation of the fort of Tafasoha in Makian Island, undated but probably executed around 1628.

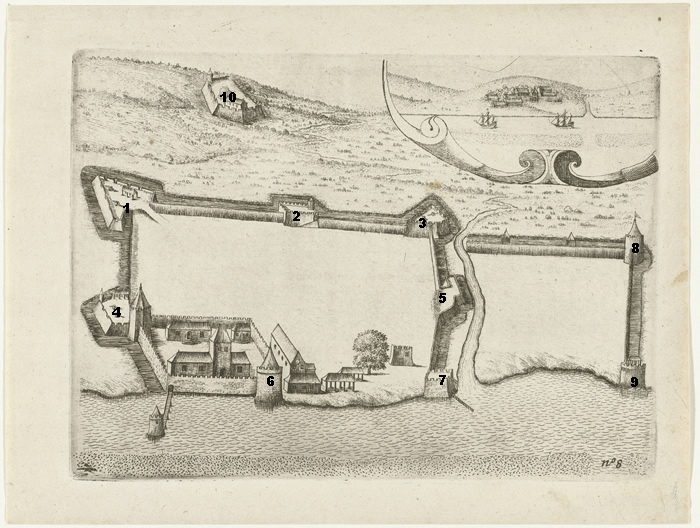

– Anonymous “Planta de le fuerza nueva que se ha de hacer en Terrenate”

1606 ?

Present in a letter from D. Juan de Esquivel dated May 2, 1606

Dimensions: 32×42 cm

Preserved in the “Archivo General de Indias” Seville: Patronato Est I, Caj 2, leg. 1/14, num. 1, ramo 19

Mentioned in the catalogue: “Relación descriptiva de los mapas, planos, etc., de Filipinas, existentes en el Archivo General de Indias. Escrita expresamente para el ARCHIVO, por Pedro Torres Lanzas” 1897 Pubblicato in Rentana.

The plan of the fort is published in “Labor Evangelica” vol. III p. 73

Map of the new Spanish fort that was to be built on a hill overlooking the city of Ternate.

– “De Stadt van Gamalama in’t Eylant Ternate, by de Spaensche beseten”

In: “Begin ende Voortgang van de Vereenighde Nederlandsche Geoctroyeerde Oost-Indische Compagnie” 1646 III, C. Matelief de Jonge, afb. 8, p.67

Also published in: Valentijn “Oud en Nieuw Oost Indie”

A representation of the fortifications of the Spanish city of Ternate.

– “Tidore” Pieter Willemsz, 1607

Tavola XVIII In: “India Orientalis” pars VIII, Francofurti 1607.

A good overview of the city of Tidore during the Dutch attack on the Portuguese fort in 1605.

– “Caart van het vervallen Casteel en stadt Gammelamme, jare1720”

ARA, VOC 1934.

An interesting reproduction of what remained of the Spanish city of Ternate in 1720.

– Reimer, Carl Friedrich “Situatieplan van ‘t Fort Oranje, behelsende de Oostelyke Kust van het Eyland Ternate, van de Lagune tot voorby Tolucco enz.”

18th century map, 760 x 1450 mm, Nationaal Archief, Collection Leupe, VEL0478.

Map of the southeastern coast of Ternate between Tolucco and the Laguna, the following place names are mentioned: Fitoe, Kalamatah, post Kajoemeirah, Kampong China, Kampong Makassar, Santoni, B’loelo Madesse, Sneero, Mootie, Fakoewe, Branka Sengaadjie, Gamsoenie, Branke Nagri Baroe, Kampong Xoela. Fonte: Atlas of Mutual Heritage.

– Ver Huell, Quirijn Maurits Rudolf “Bouwvallen van het Spaansche Kasteel, Gamma Lama. Eiland Ternate”

P 2161-52 Collectie Picturalia, Maritiem Museum Rotterdam, 1820

Watercolor representing part of the remains of the Spanish fortress of Gammalamma as they were in 1820.

BOOKS AND ARTICLES:

– AA. VV. “Het fort Oldenbarneveld te Batjan”

In: “Eigen Haard” n°21 (1883) pp. 257-258

– AA. VV. “Indonesia, a travel survival kit”

899 pp. Lonely Planet, 1990, Hawthorn, Victoria, Australia.

– AA. VV. “Spain and the Moluccas. Galleons around the world”

126 pp. Amper Ltd, 1992, Jakarta, Indonesia.

– AA. VV. “A viagem de Fernão de Magalhães e a questão das Molucas. Actas do II coloquio Luso-Espanhol de História Ultramarina”

xxv+765 pp. Junta de Investigações Cientificas do Ultramar, Centro de Estudos de Cartografia Antiga, 1975, Lisbon, Portugal.

– Andaya, L. Y. “The world of Maluku. Eastern Indonesia in the early modern period”

ix+306 University of Hawaii Press, 1993, Honolulu, USA.

– Bañas Llanos, Maria Belén “Las islas de las especias. Fuentes etnohistóricas sobre las Islas Molucas. S. XIV-XX”

160 pp. Universidad de Extremadura, 2000, Cáceres, Spain.

– Becking, C. L. “Hollandsche en Portugeesche vestigingen op het eiland Ternate”

In: “Indie GT” n°8 (1924-1925) 12 pp. 235-241

– Boxer, Ch. R. e Vasconcelos, F. de “André Furtado de Mendonça, 1558-1610”

195 pp. Fundação Oriente e Centro de Estudos Maritímos de Macau, (prima edizione 1955) 1989, Lisbon, Portugal.

– Bruijn, J. R.; Gaastra, F.S. and Schöffer, I. “Dutch-Asiatic shipping in the 17th and 18th centuries”

3 volumes: Vol. I Introduction: xi+356; Vol. II Outward voyages 1595-1794: xii+768; Vol. III Homeward voyages 1597-1795: xii+628 pp. 1979-87, ‘s Grav., NL.

– Carneiro de Sousa, Ivo & Leirissa, Richard Z. “Indonesia-Portugal: five hundred years of historical relationship”

259 pp. Centro Português de Estudos de Sudeste Asiatico, 2002, Lisbon, Portugal.

– De Clercq, F.S.A. “Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate”

1890, Leiden, NL. (English & pdf version)

– Hanna, Willard A. & Des Alwi “Turbolent times past in Ternate and Tidore”

290 pp. Rumah Budaya, 1990, Banda Naira, Indonesia.

– Labrousse, Pierre “Ternate et Tidore. Notes de voyage”

In: “Archipel” n°39 pp. 35-46

– Leirissa, R. Z. “Local potentates and the competition for cloves in early seventeenth century Ternate (North Moluccos): a preliminary study”

23 pp. Conference of the International Association of Historians of Asia (22) 7 Bangkok 1977

– Lobato, Manuel L. M. “Politica e comércio dos portugueses na Insulindia: Malaca e as Molucas de 1575 a 1605”

iv+406 pp. Instituto Português do Oriente, 1999, Macau.

– Meersman, Achilles “The Franciscans on the Moluccans 1606-1663”

In: “The Franciscans in the Indonesian Archipelago, 1300-1775”

iv+203 pp. Nauwelaerts, 1967, Louvain-Paris.

pp. 55-86

– Montero y Vidal, José “Historia general de Filipinas: desde el descubrimiento de dichas islas hasta nuestros dias”

Tomo I xvi+606 pp. Imprenta y Fundición de Manuel Tello, 1887, Madrid, España.

– Muller , Kal “Maluku: Indonesian Spice Islands”

214 pp. Periplus Edition, 1997, Singapore.

– Neyens, M. “Van een oud fort en een ondeugend opschrift”

In: “TBG” n°61 (1922) pp. 611-613

– Pastells, P. Pablo S. J. “História General de Filipinas”

Tomo I (1493-1572), Tomo V (1602-1608), Tomo VI (1608-1618), Tomo VII (1618–1635)

In: Torres y Lanzas, D. Pedro “Catalogo de los documentos relativos a las islas Filipinas existentes en el archivo de Indias de Sevilla. Procedido de una História General de Filipinas, por el P. Pablo Pastells, S. J.”

Compagnia Gen. de Tabacos de Filipinas, 1925-1936, Barcellona, Spain.

– Pérez, Lorenzo O.F.M. “Historia de las misiones de los Franciscanos en las islas Malucas y Célebes”

In: “Archivum Franciscanum Historicum” n° VI (1913) pp. 45-60, 681-701 VII (1914) pp. 198-226, 424-446, 621-653 Quaracchi, Firenze, Italia.

– Pérez, Lorenzo O.F.M. “Los franciscanos en el Extremo Oriente (Noticias bio-bibliográficas)”

In: Archivum Franciscanum Historicum n°1, (1908) pp. 241-247, 536-543; n°2, 1909 pp. 47-62, 232-239, 548-560; n°4, 1911 pp. 50-61, 482-503.

– Prakash, Om “Restrictive trading regimes: VOC and the Asian spice trade in the seventeenth century”

In: An expanding world vol. 11 “Spices in the Indian Ocean world” pp. 317-336 Variorum, 1996, UK.

– Prieto Lucena, A. M. “Filipinas durante el gobierno de Manrique de Lara, 1653-1663”

xiv+163 pp. Escuela de Estudios Hispano-Americanos, 1984, Seville, Spain.

– Rodao, Florentino “Restos de la presencia iberica en las Islas Molucas”

In: AA. VV. “España y el Pacifico” AAEP, 1989, Madrid, Spain. pp. 243-254

– Silva, C. R. de “The Portuguese and the trade in cloves in Asia during the sixteenth century”

In: An expanding world vol. 11 “Spices in the Indian Ocean world” pp. 259-268 Variorum, 1996, UK.

In: “Studia” n°46 (1987) pp. 133-156 Centro de Estudos Histórico Ultramarinos, Lisbon, Portugal.

– Stampa, Leopoldo “Las islas de Tidore y Ternate en el recuerdo historico español”

In: “Revista de historia naval” n°12 (45) pp. 21-39 (1994)

– Stokman, Sigfridus “De missies der Minderbroeders op de Molukken, Celebes en Sangihe in de XVIe en XVII eeuw

pp. 499-556 In: “Collectanea Franciscana Neerlandica (deel II). Uitgegeven bij het eeuwfeest van de komst der Minderbroeders in Nederland en van de stichting eener eigen Provincia Germaniae Inferioris”

Teulings, 1931, ‘s-Hertogenbosch, NL.

– Temminck Groll, C.L. “The Dutch overseas. Architecture survey. Mutual heritage of four centuries in three continents”

479 pp. Waanders, 2002, Zwolle, NL.

– Tiele, P. A. “De Europeërs in den Maleischen Archipel”

In: “Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde van Nederlandsch Indië” n°32 (1884) pp. 49-118 (relating to 1606-1610); n°35 (1886) pp. 257-355 (relating to 1611-1618); n°36 (1887) pp. 199-307 (relating to 1618-1623).

– Torres y Lanzas, D. Pedro “Catalogo de los documentos relativos a las islas Filipinas existentes en el archivo de Indias de Sevilla. Procedido de una História General de Filipinas, por el P. Pablo Pastells, S. J.”

Tomo I (1493-1572), Tomo V (1602-1608), Tomo VI (1608-1618), Tomo VII – 1.a part (1618–1621) e 2.a part (1622-1635), Tomo VIII (1636-1644), Tomo IX (1644-1662) Compagnia Gen. de Tabacos de Filipinas, 1925-1936, Barcellona, Spain.

The catalog of documents is also published on the CD-Rom of the Filmoteca Ultramarina Portuguesa.

– Van de Wall, V. I. “De Nederlandsche oudheden in de Molukken”

xx+313 pp. 155 ills on 93 plts & 3 maps 1928, ‘s-Gravenhage, NL.

249,12 $ (210 E)

– Van Wickeren, Arnold “Geschiedenis van Portugal en van de Portugezen overzee”

deel V, VI, VII, VIII, IX, X Hogeschool, 1999-2003, Alkmaar, NL.

– Villiers, John “Las Yslas de esperar en Dios: the Jesuit Mission in Moro 1546-1571”

Modern Asian Studies, n°22, 3 (1988) pp. 593-606

– Wallace, Alfred R. “The Malay Archipelago”

2 volumi Project Gutenberg, February 2001, Champaign, Illinois, USA.

– Wessels, C. “De katholieke missie in de Molukken, Noord Celebes en de Sangihe eilanden. Gedurende de spaansche bestuursperiode, 1606-1677”

141 pp. Drukkerij Henri Bergmans & Cie., 1935, Tilburg, NL.

– Wessels, C. “De Augustijnen in de Molukken, 1544-1546; 1606-1625”

In: “Historisch Tijdschrift” n°13, 1934 pp. 44-59

– Wessels, C. “De katholieke missie in het sultanaat Batjan, 1559-1609”

In: “Historisch Tijdschrift” n°8/1 (1929) pp. 115-148; n°8/2, (1929) pp. 221-247.

– Wichmann, A. “Von Java nach Ternate.”

In: “Nova Guinea. Bericht uber eine im jahre 1903 ausgefuhrte reise nach Neu-Guinea” Vol 4 (1917) pp. 1-49

– Zandvliet, K. “Mapping for money. Maps, plans and topographic paintings and their role in Dutch overseas expansion during the 16th and 17th centuries”

328 pp. Batavian Lion International, 2002, Amsterdam, NL.

JOURNALS:

– Boletim da Filmoteca Ultramarina Portuguesa, Portogallo.

– Itinerario, Leiden University, NL.

– Mare Liberum, Portugal.

– Oceanos, Portugal.

– Studia, Portugal

MAPS:

– AA. VV. “Schetskaart van de eilanden Tidore en Maitara”

Scala: 1:20.000 Topographische inrichting in Nederlandisch-Indië, 1916, Batavia.

Detailed Dutch map of the islands of Tidore and Maitara.

– AA. VV. “Schetskaart van de eilanden Ternate en Hiri”

Scala: 1:20.000 Topographische inrichting in Nederlandisch-Indië, 1916.

Detailed Dutch map of the islands of Ternate and Hiri.

– AA. VV. “Res. Ambon Afd. Ternate, blad 44”

Scala: 1:100.000 Opgenomen door den topografischen dienst in 1922.

Map including the northern part of Makian Island, the entire islands of Moti and Mare, and the southern part of Tidore Island.

BIBLIOGRAPHS:

– Hidalgo Nuchera, Patricio “Guía de fuentes manuscritas para la historia de Filipinas conservadas en España”

496 pp. Fundación Histórica Tavera, 1998, Madrid, Spagna.

– Landwehr, John “VOC. A bibliography of publications relating to the Dutch East India Company : 1602-1800”

Edited by P. van der Krogt, with an introduction by C. R. Boxer, and a preface by G. Schilder.

xlii+840 pp. Hes Publishers, 1991 Utrecht, NL.

1674 works described.

– Polman, Katrien “The North Moluccas: an annotated bibliography”

xx+192 pp. Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde, Martinus Nijhoff, 1981, The Hague, NL.

– Van Veen, Ernst & Klijn, Daniel “A guide to the sources of the history of Dutch-Portuguese relations in Asia, 1594-1797”

iii+378 pp. Intercontinenta Series n°24, Institute for the History of European Expansion, 2001, Leiden, NL.