Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster.

Ternate, Terrenate, Thernate, Gamolamo, Ciudad del Rosario (or Rrosario), Gamma Lamma1 : (Current name: Kastela, Benteng Kastela o Kastella) (Under Spanish control: 1 April 1606-1663)

The Spanish city of Ternate was in the southern part of the island, in the place now called Kastela, where, since 1521, were established the Portuguese, who built here their fortress of São João Bautista of Ternate and where the island’s main town was at the time of the Portuguese arrival. (See here for the Portuguese fort of Ternate)

Conquered by Ternatese in 1575, after a rebellion that drove the Portuguese from the fort, this place was conquered by the Spaniards headed by the governor of the Philippines D. Pedro de Acuña, on April 1, 1606. (See here for the Spanish conquest)

The city of Ternate was around the old Portuguese fort of São João Bautista of Ternate2, this fortification is described by Argensola as “fuerza pequeña y edificada en tiempos menos maliciosos”. The conditions of the fortress in 1606, when the Spaniards conquered it, were not the best and here they planned to improve its defenses.

A brief description of the defenses of the city of Ternate before the Spanish attack in 1606 is reported in the statements of the Dutch factor of Tidore, Jacome Joan, who, at the time of his capture, had lived in Ternate for 5 years. He described to the Spanish the state of the defenses of the city of Ternate: The height of the walls of the city was 4 “estados“, while the artillery was not inside the fort but was stored in a house to protect it from rain, also in defense of the city there were 2,000 warriors armed with muskets, rifles, “campilanes“, “petos” and “morriones“. 3

Esquivel also describes the old Portuguese fort of no use, as it is presented as “una casa de muralla” without any resistance to the artillery and also a great “padrastro” on the side toward the volcano, which dominated from above the fort, which made it virtually indefensible, so that it could be useful only as a place to live, but certainly not as a defensive position. The only defenses of the city were the two walls located on opposite sides of the city, each wall had two bastions “dos ….. rredondos” between the two walls ran an area of more than 2,000 “pasos“. Along the sea there was a land, that Esquivel defines as “pestilencial“.

In the city of Ternate the Spaniards found 43 “piezas grandes de bronce“, “peças de colher“, more than 20 “falcões” and a large number of “Bercos“4. Much of the artillery found was of Portuguese origin, most likely the one captured by Ternatese in 1575, but there was also artillery of Dutch and Danish origin. The conditions of the fortress were not the best, in this regard the Spaniards planned to improve the defenses immediately.5

In Ternate, where the old fort is small and not very defensible, it was decided to build a new stronghold in a “parte eminente, mayor y más fuerte“. Unlike what it says Argensola6 , namely that the new fort (Fuerza Nueva) before leaving for Manila Acuña was already finished and equipped with ramparts and the old fort had been reduced to “un breve sitio“, it seems that the new fort was still to be built and the old one was in poor condition.

The place where had to be built the new fort was at the back of the old fortress, right on the “padrastro” (stony hill, rocky eminence) which dominated the city, here the terrain and the dominance was deemed perfect for the construction of the new fortress. According to Acuña’s orders the fort to be built was to be square in shape, “que tenga de centro 600 pies“, and have three bastions. 7

The town around the old Portuguese fort was called by the Spaniards “Ciudad del Rosario” (Nuestra Señora del Rrosario de Terrenate). The fortress of Ternate was surrounded, on the orders of Juan de Esquivel, by a wall of earth and fagots with bulwarks well distributed.

The construction of the fortifications went slowly because of lack of money and manpower. In fact not more than 100 “gastadores” among them carpenters, masons and blacksmiths could participate in the works. Esquivel tells us that he had built and almost completed a wall of “tierra y fagina” of a 20-feet base, with which the city of Ternate was enclosed. He urgently demanded to send “gastadores” to complete the fortifications. In 1607 Esquivel sent a plant of the fortifications of the city of Ternate to the King of Spain adding “de esta tengo casi ya çerrado el lugar en la forma que V. M.d. mandara ver por una planta que va con esta” 8

In 1609 Vergara began the improvement work of the fortifications of the city of Ternate replacing the walls of “fajina” with walls of “cal y canto“. Testimonies from 1610, describing the city and the Spanish fort as built of mortar and stone, with a population of 200 Spaniards, 90 papangers, 70 or 80 Chinese artisans, 30 Portuguese casados with their families and 50-60 Ternatese Christians also with their families. 9 Azcueta during his rule (1610-1612) built around the city a strong wall of lime and stone to which he added at intervals several bastions. 10 To confirm this in June of 1610 the Dutch admiral Caerden judged the fortifications of the Spanish city invulnerable. Therefore the work undertaken by the Spanish had to be well underway. 11

The fortifications to defend the main Spanish settlement of the Moluccas were formed by a wall that ran around the city, reinforced by six bastions well distributed along the perimeter of the wall. On these bastions were mounted twenty pieces of artillery in bronze. Furthermore, on the outside of this circle of walls, were other ramparts to defend the native quarter. The troops defending the city were usually composed of 300 Spaniards (casados and soldiers), 150 pampagos and 100 indigenous Christians. The total population of the Spanish town was about 2000 people, all Christians. For their spiritual care there were three monasteries of the main religious orders: Jesuits, Franciscans and Augustinians besides the church “matrix”. 12 In 1627 the equipment of artillery of the town consisted of 38 guns of metal, while the fort’s garrison was composed of 4 companies of soldiers, each consisting of 60-65 soldiers. 13

After almost 60 years, this fort was abandoned and destroyed by the Spaniards in 1663, but part of the fort was later used again by the Dutch, who stationed a small garrison here.

Kastela, as the village is called today. The few remains of the ancient city of Ternate are described by De Clercq in “Bijdragen tot de kennis der Residentie Ternate, 1890” p. 16, as a rocky relief, which derives its name from the ruins of the fortress of Gam Lamo, first occupied by the Portuguese and later by the Spaniards.

Now we describe more in detail, what were the defenses of the Spanish city:

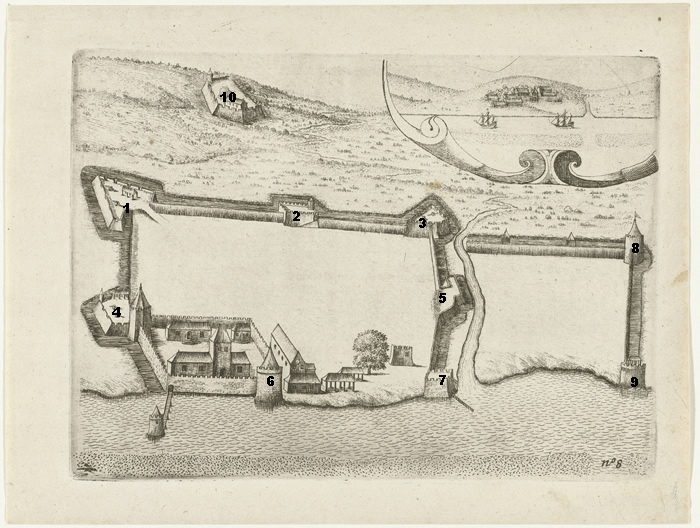

Bulwarks of the city of Ternate (Nuestra Señora, San Felipe, San Lorenzo, San Juan, Santiago, San Cristoval, Cachil Tulo):

The city of Ternate was surrounded by a wall reinforced with 6 bastions, at an angle of the wall, the most westerly, along the sea, was the old Portuguese fort. It is not easy to identify the names of the ramparts, but some Spanish documents give us some information about them.

The three ramparts: Nuestra Señora, San Felipe and San Lorenzo are the bulwarks of the city of Ternate, which were along the sea, this can be deduced from the description of a Dutch attack of the city described in a letter of Geronimo de Silva. 14 In this document are described in succession the names of the bastions that respond to the attack of the Dutch galley. They are indeed San Lorenzo, San Felipe and Nuestra Señora. As the bastion of Nuestra Señora was located in front of the bar of the same name, on the eastern side of the city, the bastion San Felipe is the name of the central bastion and San Lorenzo is the bastion of the western side.

At the time of the abandonment of the Spanish garrisons in the Moluccas, in 1663, the “certificación” written by Governor Francisco de Atienza Ibáñez and dated (inexplicably) December 10, 1666, describes the work of dismantling of the fortifications and the destruction of buildings in the city of Ternate. In this document the names of the bastions and the Spanish forts, which were demolished are indicated: the bastions of San Felipe, San Xpoual (= San Cristóval), Santiago, San Agustin (it is most likely the name of the old rampart of Cachil Tulo), San Juan, San Lorenzo, San Pedro “retirada della” (i.e. the fort built on a hill overlooking the city, which will be described later) and the “cubo” of Nuestra Señora. At the same time the baluarte Don Xil (Gil) and the fort of San Francisco Calomata were also demolished, while the houses, the churches and convents of the city of Ternate were burnt. 15

1- San Juan

2- Santiago

3- San Cristoval

4- San Lorenzo

5- Cachil Tulo

6- San Felipe

7- Nuestra Señora

8, 9 – San Antonio, San Sebastian

10- San Pedro (Fuerza Nueva)

Nuestra Señora: sea side, east

This bastion was built by the Portuguese. Probably at the time of the expedition of Villalobos. 16

During the attack on the city of Ternate in 1603 by Portuguese-Spanish troops of Gallinato and Mendoza, the bastion of Nuestra Señora is described as a bastion of stone (“caballero de piedra“) located on the side facing the sea, at the foot of this rampart was a ravelin with 7 large pieces of artillery. The bastion was completely levelled with the help of the Dutch and was “de alto de 4 braças y una media de ancho“. On the land side a wall of earth connected the bastion of “Nuestra Señora” with another bastion called “Cachiltulo“. 17

Bulwark (“Cavallero“), but also called fort, watching the entrance of the channel of “Nuestra Señora“, the only navigable channel of the barrier reef located opposite the city of Ternate. 18 Juan de Azebedo (Azevedo), was commander of this fort “en tiempo que el enemigo Olandes, y Ternate estaua sobre el”. 19 The rampart of “Nuestra Señora” is among those mentioned by Atienza in his “Certificacion“, he ordered to demolish among other bulwarks also the “cubo” of Nuestra Señora, “que era guardia de la barra”. 20 This bastion was rebuilt again “desde los cimientos” in 1651 by Governor Francisco de Esteybar. He indicates that the bastion was situated outside the walls of the main fortress of Ternate “que está extramuros de dichas fuerzas principales y barra de ella“. 21

San Felipe (Phelipe): sea side, center

Fuerte de San Felipe. 22

San Lorenzo: sea side, west

Fuerte de San Lorenzo. 23

San Juan, San Joan:

Azcueta built this fortress, which is defined as a good bulwark, which controlled on one side the beach and on the other side a hill. 24 During the government of Pedro Fernández del Rio (1642-1643) was completed the construction of the “Cavallero” San Juan with his “reuellin“, the powder magazine and the platform, this bulwark was the one which controlled the side walls to the countryside “que barre todo el lienzo que mira a la campana”. 25

Santiago, S.Tiago:

Near the bastion San Cristoval. This bastion was rebuilt in “cal y canto” in 1650 by Governor Francisco de Esteybar, who made it unvulnerable. 26

San Cristoval, San Xptoual:

Described as “baluarte grande” by Azcueta, in his letter of July 29, 1610, he indicates that bastion as already finished. A wall, still in the process of completion, united it with the bastion of Santiago. Here Azcueta had taken 4 pieces of artillery captured from a Dutch vessel. The same Azcueta informs us that this fort was also known by the name of San Pablo. 27

Cachil Tule, Cachiltulo, Cachil Tulo:

According to Argensola, the bulwark (cavallero) of Cachil Tulo was so named because it was built by the uncle of the sultan, Cachil Tulo. 28 Gallinato in his letter to Acuña of 1603, describes the “baluarte Cachiltulo” as a bastion of stone which had been reinforced by external wooden beams, mounted on the ramparts were 3 very large pieces of artillery, while other 2 pieces of artillery were mounted on the wall, which connected it with the rampart of “Nuestra Señora”. 29

During the government of Pedro Fernández del Rio (1642-1643) were reinforced the wall on the side “que mira ala parte del enemigo” whose thickness was increased to 4 feet. On the same side was also reinforced the “Cavallero” of the Cachil Tule which controlled this part of the wall and it was also to defend the native village, which was located outside the walls. 30 This bastion was probably later called San Agustin. 31

Bulwarks “extramuros” of the city of Ternate (San Antonio, San Sebastian):

These two bastions, in defense of the indigenous village of Ternate, were built in 1613, during the government of Gerónimo de Silva. 32

Near the town the Spaniards built another fort: Fort San Pedro (Fuerza Nueva).

[divider]

NOTES:

1 “Traslado de carta de Sabiniano Manrique de Lara” Arch. Gen. De Indias, Filipinas, 9, R.2, N.34

2 The Portuguese fort was founded by António de Brito in 1522, the foundation stone of the fortress was laid for the feast of St. John the Baptist, June 24, 1522, the fort was named “São João Bautista de Ternate“. (See here for the Portuguese fort of Ternate)

3 “The Dutch factory at Tidore” In: Blair, EH and Robertson, JA “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 14, pp. 112-118. See also the document version date Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” Volume V, pp.. ccxx-ccxxi

4 Argensola, B. Leonardo de “Conquista de las islas Malucas al Rey Felipe Tercero”

(first edition 1609, Miraguano Ediciones & Ediciones Polifemo, 1992, Madrid) p. 329. See also “Letter of Acuña to the King, 8 april 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo V, p. ccxxiii. While in Jacobs, H. “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” p. 8 Doc. n°1: “40 peças de colher”, more than 20 “falcões” and a great number of “berços”.

5 Doc.Mal. III p. 8 Doc. n°1. For a detailed list of artillery found in Ternate see: Pastells “Historia general de Filippines” tomo V, pp. ccxxvii-ccxxviii

6 Argensola, B. Leonardo de “Conquista de las islas Malucas al Rey Felipe Tercero”

(first edition 1609, Miraguano Ediciones & Ediciones Polifemo, 1992, Madrid) p. 345

7 “Letter of Esquivel to the King, Ternate, May 2, 1606” in Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” Volume V, p. ccxxix-ccxxx. Colin-Pastells “Labor evangelical” vol. III p. 56 note 1

8 AGI: Patronato, 47, R.22 “Carta de Juan de Esquivel al Rey progresos islas del Maluco, 31-03-1607”

9 van de Wall, V. I. “De Nederlandsche oudheden in de Molukken”

p. 258

10 Gregorio de S. Esteban “Historia de las Malucas” p. 50 reported in: Perez “Malucas y Celebes” p. 214

11 de Booy “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden uitgezeild in 1606” vol. II p. 239 “Copie van het scrijven van Paulus van Caerden aan de bewindhebbers dd. 17 juni 1610”

12 Doc. Ultr. Port. Vol. I p. 164 “Relação breve da ilha de Ternate, Tydore….” Malaca, 28 november 1619

13 van de Wall, V. I. “De Nederlandsche oudheden in de Molukken”

p. 258

14 Correspondencia, May 2, 1612, p. 19

15 AGI “Carta de Manrique de Lara sobre asuntos de guerra” “Traslado de carta de 9 de diciembre de 1662 de Sabiniano Manrique de Lara, al gobernador de las fuerzas de Terrenate, comunicándole la decisión de retirar las fuerzas que guarnecían aquel presidio para resistir a Cogsenia, tirano de las costas del reino de la china y dándole instrucciones sobre las diligencias que había de hacer con el gobernador holandés de Malayo para garantizar la propiedad y dominio español sobre esos puertos y plazas; diligencias hechas por el general Francisco de Atienza Ibañez, a quien se acometió la retirada, y relación del estado en que quedó dicho presidio.1667,mayo,6.”(Cat.20890) Filipinas,9,R.2,N.34

16 Consuelo Varela “El viaje de don

Ruy López de Villalobos a las islas del Poniente, 1542-1548” pp. 185-191

17 “Letter by Gallinato to Acuña, 24 May 1603” A.G.I. 67-6-7 In: Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo V p. clxi

18 Jacobs, H. “A treatise on the Moluccas (c. 1544)” p. 361 nota n°11

19 AGI “Meritos: Juan de Azevedo, 1625” Indiferente, 111, N.56

20 AGI “Atienza. Certificación” 67-6-9

21 AGI “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc Francisco de Esteybar [c] 1661-12-17” imagen 86 and 115. Filipinas,51,N.14)

22 Various authors “Correspondencia de D. Jeronimo de Silva con Felipe III, D. Juan de Silva, el Rey de Tidore y otros personajes, desde abril 1612 hasta febrero de 1617, sobre el estado de las islas Molucas” In: “Coleccíon de documentos inéditos para la historia de España” vol. n°52, 1868, Madrid. Pag. 19

23 Various authors “Correspondencia de D. Jeronimo de Silva con Felipe III, D. Juan de Silva, el Rey de Tidore y otros personajes, desde abril 1612 hasta febrero de 1617, sobre el estado de las islas Molucas” In: “Coleccíon de documentos inéditos para la historia de España” vol. n°52, 1868, Madrid. Pag. 19

24 Gregorio de S. Esteban “Historia de las Malucas” p. 50 passage reported in: Perez “Malucas y Celebes” p. 214

25 AGI Meritos: Pedro Fernández del Rio, 1647” Indiferente, 113, N.50

26 AGI “Confirmación de encomienda de Abucay, etc Francisco de Esteybar [c] 1661-12-17” imagen 86 and 115. Filipinas,51,N.14

27 AGI “Cartas del Virrey Luis de Velasco (El Hijo),1607-1611” Carta de Azcueta: “El Sargento Mayor Cristóbal de Azcoeta al Gobernador de las Filipinas Don Juan de Silva, sobre el estado de las fuerzas a su cargo, Fuerza de Terrenate, 23-IV-1610 ”8fs.” México,28,N.2

28 Argensola, B. Leonardo de “Conquista de las islas Malucas al Rey Felipe Tercero” (first edition 1609, Miraguano Ediciones & Ediciones Polifemo, 1992, Madrid) p. 158

29 “Letter by Gallinato to Acuña, 24 May 1603” A.G.I. 67-6-7 In: Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo V pp. clxi-clxii

30 AGI “Meritos: Pedro Fernández del Rio, 1647” Indiferente, 113, N.50

31 AGI “Carta de Manrique de Lara sobre asuntos de guerra” “Traslado de carta de 9 de diciembre de 1662 de Sabiniano Manrique de Lara, al gobernador de las fuerzas de Terrenate, comunicándole la decisión de retirar las fuerzas que guarnecían aquel presidio para resistir a Cogsenia, tirano de las costas del reino de la China y dándole instrucciones sobre las diligencias que había de hacer con el gobernador holandés de Malayo para garantizar la propiedad y dominio español sobre esos puertos y plazas; diligencias hechas por el general Francisco de Atienza Ibañez, a quien se acometió la retirada, y relación del estado en que quedó dicho presidio.1667,mayo,6.”(Cat.20890) Filipinas,9,R.2,N.34

32 Pérez, Lorenzo O.F.M. “Historia de las misiones de los Franciscanos en las islas Malucas y Célebes”

In: “Archivum Franciscanum Historicum” n° VI (1913) pp. 45-60, 681-701 VII (1914) pp. 198-226, 424-446, 621-653 Firenze. Pag. 221