This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano ![]() Indonesia

Indonesia

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster.

4.0 THE SPANISH FORTS ON THE ISLAND OF TIDORE, 1606-1663

As we mentioned earlier, from April 1606 after the conquest by the troops of Acuña of the city of Ternate, the Spaniards had, in the Moluccas, as their main and often the only ally the King of Tidore. They tried for several decades to counter the growing power of the Dutch armies, occupying some islands with fortified garrisons. The island of Tidore played a key role between them.

After the Spanish conquest of Ternate the King of Tidore had offered to Pedro de Acuña the subjugation of his kingdom to Spain and had also promised the construction of a Spanish fortress on his island. Acuña, in fact, at the time of his departure had ordered among the works to be carried out urgently the construction of a Spanish fort on the island of Tidore and according to this order a captain with some Spanish soldiers had to be stationed there. 1

This order, as we shall see, however, will not be executed by Juan de Esquivel, appointed by Acuña as governor of Ternate. The alliance with the king of Tidore for many years was essential for the maintenance of Spanish presence in the Moluccas. Indeed, at first, Acuña wanted to put the king of Tidore at the head of the kingdom of Ternate. 2

The importance for the Spanish of the island of Tidore is clearly described by the words of Pedro de Heredia: ‘…se si desmantelara la fuerça de Tidore no tuuiera el Rey nuestro señor en muy breue tiempo palmo de tierra que fuera suyo por ser plaça tan importante…’ ‘…pues sin aquella plaça no se podia conseruar un mes la de Terrenate…’ 3 In fact, even Gerónimo de Silva considers Tidore crucial to the livelihood of Spanish Ternate, because in addition to being the king of Spain’s main ally, the island was supplying Ternate with ‘… viandas de pescado y gallinas, y otras vituallas que de allá se traen.’ 4

Again Gerónimo de Silva judges, in another letter, the island of Tidore, the most important of the Moluccas, and from which come the supplies needed for the livelihood of the city of Ternate.5 Concerning the production of cloves, the island was producing it in small quantities, small compared to the amount produced in the islands of Maquien and Motiel, fully controlled by the Dutch, ‘Y es muy poco en comparación del que tienen los holandeses en las islas de Maquien, y Motiel que estan tambien de uaxo ala equinoxial, y muy cercanas, y vecinas a Terrenate, y Tidore.’6

However, among their possessions, it was only the island of Tidore, which the Spaniards obtained a quantity of cloves ‘… Tidore da un año con otro cuatrocientos bases’ that is, 2400 quintals, compared with a total production in the Maluku islands, estimated by Gerónimo de Silva at 9000 quintals “mil y quinientos bases de clavo que son nueve mil quintales”.7 Starting from 1613, with the loss of the Fort of Marieko, the production of cloves controlled by the Spaniards will be even more insignificant, Marieko, in fact, was located in the most productive part of the island.

Critical is also the market management of cloves made by the Spaniards. Gerónimo de Silva infact is clear on this point, the amount in the hands of the Spaniards, although small, could, if traded, as do the Dutch, through a farm controlled by the King, could make 30,000 ducats, if traded in India, but would make even more, if traded directly to Europe, while with the existing system, operated by private persons, the Spanish crown did not receive any annuity. If the Spanish could have their hands full in the production of cloves of these islands, there would be about 1500 “bases de clavo“, that is nine thousand quintals a year and they might get, if sold directly to the European market, 150,000 ducats a year.8

The importance of Tidore and of the alliance, which the Spaniards maintained with the king of the island, was also very clear to the Dutch, who, especially in the early years, repeatedly tried to drive the Spaniards from the island: as early as May 1607 the fleet of Cornelis Matelief 9 designed to attack Tidore. For this purpose a boat to call for reinforcements was sent to the Ternatese rebels. The Dutch, despite the meager arrival of reinforcements, a boat with about 200 warriors, who arrived with the young sultans of Ternate and Jailolo, however, decided to attack the island, which was defended initially by thirty Spanish soldiers in addition to the Tidorese. The landing was attempted on some boats and ‘caracoras’, on which were embarked about 300 soldiers, but the reception by the Spaniards and Tidorese was hot and the attackers were forced to retreat with several losses. The attempt ended poorly for both. The inexperience and unfamiliarity with the seabed by the Dutch was great, because the boats were in danger of overturning in the barrier and the governor Juan de Esquivel promptly rescued the island with some Spanish soldiers ‘… con cierto golpe de españoles, …’. After this episode Matelief refolded on Ternate, where he founded the fort Malayo. 10

On 16 June 1608 a new Dutch fleet (according to Esquivel participated in the attack: seven ships, a galley and a pataco) commanded by van Caerden, and aided by a contingent of 26 boats and many Ternatese soldiers, anchored in front of the old Portuguese fort of Tidore with the intention to attack and conquer the city, but the defenses prepared by the Tidorese and the Spaniards the attackers retreated, after having stayed about twenty days at anchor in front of the old Portuguese fort. They changed their goal by attacking the island of Makian.11

After the attempted attack on Tidore led in June by the Dutch, the Spaniards were compelled to reinforce the garrison of the island. In August 1608 the Spaniards at Tidore were composed of 140 soldiers and a galley with another 40 soldiers on board with a total of 180 men.12

During the government of Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, between the end of 1609 and January 1610, another abortive attempt to besiege Tidore was made by the fleet led by Simon Jansz Hoen, who simply run for a naval blockade of the island of Tidore and attack and capture the Spanish fort on the island of Bachan.13

The Jesuit Jorge da Fonseca, designed for the spiritual care of the Spanish garrison at Tidore, 14 describes the island of Tidore in his letter of April 8, 1612: ‘… que hé huma ilha quatro legoas de Ternate, de mouros amigos nossos, onde há alguns christãos da terra, portuguezes casados e hum presidio de soldados hespanhoes, que todo este tempo atrás avia estado sem padre por falta de sacerdotes’.15 The Jesuit mission of Tidore was in fact until the end of 1610 without a father, later in his letter Fonseca describes Tidore again, this time making reference to two Spanish forts on the island.16

The existence of two forts there are further enhanced by “Correspondencia” by Geronimo de Silva, according to which, in 1612, the Spaniards occupied with their garrisons two forts on the island of Tidore 17, the two garrisons were the old Portuguese fort, near the town of Soa Siu and the fort in Marieko on the west coast, they had been reinforced and improved by the governor Vergara in 1609. In the following years because of the increasing pressure of the Dutch on Tidore, the Spaniards were forced to increase the forts and to garrison troops on the island and to abandon some strongholds on the outer islands of Morotai and Halmahera (in the middle of 1613 were abandoned the forts of Sabugo (May-July 1613) and San Juan de Tolo (August 1613)).

The year 1613 is the year when the Dutch tried several times to expel the Spaniards from the island permanently, with attacks towards Marieco and the fortifications of the main city of Tidore. In February 1613, the Dutch captured the fort of Marieco, rebuilt it and placed a strong garrison there. This fort was a thorn in the side of the Spanish until it was abandoned by the Dutch in 1621/1622. After the loss of Marieco, the Spaniards ran for cover, sending two companies of 100 soldiers each to Tidore, they were commanded by Captain Don Diego de Quiñones and by the ensign Don Fernando Becerra, who commanded the company of Captain Pedro Zapata.18

A part of the soldiers destined to Becerra were, however, diverted to other garrisons, because, according to the testimony of Sergeant Fernando de Ayala, Becerra had twenty soldiers under his command with the ensign Arrequibar and the total of Spanish troops present at Tidore, counting the soldiers of Don Diego de Quiñones was 119 soldiers excluding officers.19 A new fort called ‘Marieco el Chico‘, located in the vicinity of the fort of Marieco occupied by the Dutch, was garrisoned by Spanish troops. Also the fort of Socanora, located south of the capital of Tidore was garrisoned by a small Spanish garrison.

In July 1613, the Dutch and the Ternatese undertook their largest attack directly to the town of Tidore, where they could capture the old fort of the Portuguese, while several subsequent attacks against Socanora and the town of Tidore resulted in many failures for the Dutch, who then were forced to abandon the only conquest they made: the fort of the Portuguese.

In an interesting letter written by the king of Tidore, Cachil (Kaicil) Mole, July 9, 1613, the day of the conquest by the Dutch of the fort of the Portuguese, the King pointed out to the governor of Ternate, Gerónimo de Silva, his whole concern for the desperate situation of the Spanish and Tidorese troops in Tidore also due to the scarcity of food and supplies, the king called for the immediate sending of more Spanish troops, in his letter he came also to envisage the abandonment of the island and the withdrawal of all people in Ternate “ó inviar aquí mas españoles, ó que nos vamos todos á Terrenate”. 20

The continuous state of war between the Dutch and Spaniards, and among their allies ternatese and tidorese led to an impoverishment of the land and population, which was also noticed by the casual visitors like the English John Saris, who stopped for a few days in Tidore during 1613, which expressed its regret on the lamentable state of destruction brought to the islands by the continuous wars.21

To indicate the importance which the Spaniards gave to the Tidore is that under the precise order of Juan de Silva also the governor of Ternate, Gerónimo de Silva, in late 1614 moved to Tidore, he will reside on the island, in the new fortress (Santiago de los Caballeros or Tahula) built by the Spaniards, for long periods in the years 1615 and 1616.22

In subsequent years the state of war between two rival European powers is to persist, but apart from a few skirmishes, the Dutch will not attempt more attacks such as those brought on a large scale in 1613, for they will change tactics, trying to interfere in relations between the Spaniards and tidorese and to undermine the alliance between the two. Especially they come near the Prince of Tidore, who was madly in love with the Queen of Jailolo, trying to get him on their side.

However, even after 1613 the Spaniards were forced to constantly maintain a strong garrison on the island. In the middle of 1616 there were more than 200 Spanish soldiers to garrison the forts of Tidore, and that in the forts of Santiago, del Príncipe, Tomanira and Socanora.23 “…por las pocas fuerzas que hoy tiene el rey de Tidore, por ser muy solo y no tener en su isla lo que tenia hasta aqui, por lo que me conviene tener siempre en esta isla sobre ducientos hombres en la plaza de Santiago y en el fuerte del Principe, Tomanira y Socanora“.24

In May 1619 the governor of Ternate, Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, informs us that the Spanish island of Tidore has four forts: Tohula, Tomanira, Sokanora and the new fort of San Lucas de el Rume. The forts in Spanish hand, Vergara informs us, dispose of one third of a normal garrison.25 This lack of troops is a constant throughout the period of Spanish control of the island.

The Dutch who occupied from 1613 the fort of Marieco between 1621 and 1622 dismantled and abandoned it. The entire island as of this date and until almost the final abandonment by the Spanish troops in 1663 remained under the control of the Spaniards and their Tidorese allies. The Spaniards kept on the island of Tidore until the last years of their presence the following three forts: Rume, Taula (Tahula) and Sobo (Cobo, Chobo). 26

In the following years as well as with the Dutch, the Spaniards had some serious problems and different crises in relations with their closest ally, the king of Tidore, especially between 1636-1640 and most severely in the years around 1655-1660, when the island of Tidore remained in a state of constant rebellion. The first period of crisis coincided with the usurpation of the kingdom by cachil Naro, and the accession to the throne of Tidore by cachil Borotalo, endorsed by the Spanish Governor Pedro de Heredia.

The situation was resolved thanks to the steadfastness of the new governor, Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola, called in to replace Pedro de Heredia. He came to Ternate with the specific order to put on the throne the rightful king of Tidore, the cachil Naro, who had been unjustly deprived of his crown by Pedro de Heredia, who had put in his place the cachil Borotalo (cousin of the king cachil Naro).

It seems that Heredia had had friction with cachil Naro regarding the sale of cloves, because of this Pedro de Heredia influenced the Tidorese to abandon him and swear allegiance to cachil Borontalo, his cousin. Cachil Naro was then forced to take refuge with the Dutch in their fort of Malayo. For this and other reasons it was later decided to open legal proceedings against the actions of Pedro de Heredia. The cachil Naro is described as a man loyal and brave and always loyal to the Spaniards.

The new governor Pedro de Mendiola was ordered to put in place cachil Naro, which for the moment he could not do, because cachil Naro had taken refuge at the Dutch fort Malayo. This was the situation, Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola found, when he came to rule in Ternate. He had received strict instructions from the governor of the Philippines Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera to restore legality, secretly contacting, by letter cachil Naro, who was exiled to Malayo, but now ordered to Ternate to be put back in place as the king of Tidore, since Pedro de Heredia had no authority to take away the kingdom.

As for what would be the moves of the Spaniards to reconnect with cachil Naro and put him back on his throne, there is an interesting document signed by the governor of the Philippines Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera: “Orden e instrucción que los generales Pedro de Mendiola, gobernador de Terrenate y Jerónimo Somonte, capitán general de la armada real an de guardar en razón de la restitución del rey Cachil Naro a su reino, Cavite January 8, 1636”.

In the document, which displays the Spanish plans, it appears that, once arrived in Ternate, Mendiola was secretly contacting cachil Naro and invite him or on a Spanish galleon or in the city of Ternate, guaranteeing the security through cards of the governor, once cachil Naro came to talk with Mendiola, the governor had to be pointed out the regret he had for the actions of Pedro de Heredia, who had not helped with the Spanish arms cachil Naro to defend himself against his opponents and had allowed him to be deprived of his kingdom.

The Spaniards now wished to remedy this by providing their troops to resettle cachil Naro in Tidore, provided, he acknowledges the Spanish aid and alliance with the Spaniards. The Spanish proposal was to unite the Tidorese in remaining faithful to cachil Naro along with the Spanish troops and take possession of the kingdom. The agreement was to be provided by an official pact between the two Spanish generals (Pedro de Mendiola and Jerónimo Somonte) and cachil Naro.

After reaching the agreement with cachil Naro, the document describes the moves to be made against the usurper. The first move was to release cachil de Reues so that he could give to his king cachil Bontalo (Borontalo) a card inviting him to the Spanish castle, where he was to be entertained with kind words and gifts before the cachil Naro would arrive to take over and occupy Tidore. These operations were important, keeping them secret, nobody except the Spanish sergeant Juan Gonçales de Caceres Melon, and the captains don Pedro de Almonte, Sebastian Bauptista and Pedro de la Mata had to be made aware or even suspect something of what was preparing.

If things took the course hoped and cachil Naro was put back on his throne, General Geronimo de Somonte was to bring the king deposed cachil Borontalo to Manila, where he could get justice before the Audiencia and the governor and if proved his own reasons may be restored in the kingdom, although he must have made it clear that Pedro de Heredia had no right to depose cachil Naro and it was not possible for a Spanish officer at will depose a King ally, indeed, if this had been tried, Heredia risked his life for his actions.

Once the issue resolved and settled cachil Naro on the throne of Tidore, the new king had to be requested to provide to the Spaniards the usual 4 or 6 ‘caracoras’ with 400 Tidorese , who had to

receive the same pay as soldiers pampangas of the garrison. The instructions also included the possibility of the request for caracoras and men for the case cachil Borotalo would remain in power .27

So far the plans of the Spaniards, but the absolute secrecy, basic thing of the whole operation, was not kept, because, cachil Borontalo had to be learned about the intentions of the Spaniards and at his request, the Dutch and the ternatese treacherously killed cachil Naro, it seems that cachil Borotalo had promised to the Dutch to build a fort on the island.

Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola was able, however, to scare away (say documents with great difficulty) from Malayo, the son of the cachil Naro and his legitimate heir, cachil Sayde. The Spaniards then decided to lay cachil Borotalo and settle as King the son of the late King cachil Naro, the cachil Sayde. Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola acted with caution and managed to prevent the designs of the usurper King, managing to surprise him on his own island home and punish him as a traitor, managing to kill him stabbed. So he could carry out the orders he had received to capture or kill cachil Borontalo. All this was done by Sergeant Major Francisco Hernandez and by the ensign Bernaue de la Plaza, who was given as a reward a company. Thanks to this the entire island of Tidore was pacified and the rightful king cachil Zayde, son of cachil Naro, was enthroned, all the Tidorese leaders performed again an act of submission to the Spanish crown.

About this episode it is interesting to note that not all Spaniards approved, what had happened, in fact, some charges were raised in 1640 ‘me tomò residencia de dhos cargos’ by Sergeant Pedro Arias de Mora, against Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola, on his conduct of government in Ternate. Of the 5 accusations reported by Arias de Mora, the fifth charge was that Carmona y Mendiola did not keep good friendship with the king of Tidore cachil Borotalo, who instead Carmona y Mendiola ordered to kill and was then stabbed to death without trial and without having tried the crime of treason, of which he was accused. All the charges were, of course, rejected by the governor of the Philippines Sebastian Hurtado de Corcuera (he was the instigator of the whole operation), who acquitted Carmona y Mendiola of all charges.28

The second crisis period was much more severe and lasted from the end of the reign of cachil Sayde until 1659. It all started with disputes between cachil Sayde, king of Tidore, and the Dutch, when cachil Calomata was elected Sultan of Ternate by some Ternatese, who rejected the legitimate Sultan cachil Mandaraja. The cachil Sayde, king of Tidore, who seems to help the rebels covertly, something he was not allowed to do, because as a subject of the King of Spain he was bound by the terms of the peace treaty, concluded between Spain and Holland.

The Dutch protested strongly against Cachil Sayde, who was for a certain period of time put under arrest by the Spaniards and then the rebellion was quelled. Then Cachil Sayde died and some Tidorese rebels elected in his place Cachil Golofino, who was general of the sea of Cachil Mandaraja and ally of the Dutch, thus rejecting the legitimate heir to the throne of the kingdom of Tidore, who was cachil Mole, son of cachil Sayde, who was supported by the Spaniards. But the rebels were assisted with weapons and supplies from the Dutch in violation of articles of the peace treaties concluded.29

The most serious moment coincided with the so-called rebellion of the ‘Moors’ of Toloa, which reached its zenith in the years 1657-1658, when the Tidorese rebels put under siege the Spanish garrison of Tidore for almost a year. Some documents are describing interesting facts of this period: an order, signed by Governor Diego Sarria Lascano and dated Tidore, March 12, 1657, provides us with interesting information about the rebellion of the Tidorese in 1657, which is defined in another document: ‘alzamiento de los moros de los pueblos de Toloa‘.

The document discusses the organization of a punitive expedition against the rebels, because of the seriousness of the situation, the governor Diego Sarria Lascano, had come in person to Tidore to plan the expedition. In the document Captain Alonso Lossano, head of the fort of ‘Santiago de los Caualleros‘, leaving the command of Spanish and pampanga infantry, receives the order to go with the troops of the king of Tidore, a friend and confederate of the Spaniards, to punish some vassals of the king of the villages of Toluca and Tongoiza, who had rebelled.

Once arrived at the place, which had been identified and selected at the meeting (meeting of council of war, which had apparently preceded the expedition), the Spaniards were to occupy and fortify in the best possible way, because this place was to be the main base of the Spanish forces during the operations; in the fort had to be positioned at least two pieces of artillery and a good garrison. Then, the fortification of the outpost completed, the captain along with a troop of soldiers had to take another place, which was strategically located above the rebels’ village, in which they had to fortify and put a garrison of soldiers. To garrison these outposts the captain could take many soldiers from the fort in Tomanira, where was in command the assistant Francisco Peres; the latter fort would still remain well-defended. The aim of the expedition was to reduce the rebels to obedience by force or bring them to sue for peace and to establish submission.30 The expedition, led by Captain Alonso Losano, was not quickly realized, in fact, the campaign for the subjugation of the two villages lasted over two months, during which the Spaniards burned and destroyed two enemy villages and then attacked and captured an enemy fortress, after this victory the Spaniards retreated to their fortress of ‘Santiago de los Caualleros’.31

The above expedition of March 1657 did not solve the issue, in fact subsequently there occurred more clashes with the rebels, who even besieged the Spanish fortress of ‘Santiago de los Caballeros’.

Another document tells us of some of the events that occurred during the siege, during this long period of war, the Spanish soldiers to garrison the fortress of ‘Santiago de los Caualleros‘ suffered hunger for the shortage of food caused by the continuous war against the Dutch, the Ternatese and Tidorese rebels. As the garrison of the fort was without food and without the ability to receive it from Ternate, because of the siege, to which they were subjected by the enemy, Joseph de Garces (who was in charge of the fort) decided to attack with a force of infantry a village of the enemy to raid the food. For this purpose Juan Rodríguez de Origuey was sent with two other soldiers on reconnaissance, they were able to spy on enemies and managed to catch one enemy and to have information, which then led to the conquest and capture of the enemy village. With the food found in the village the Spaniards were able to sustain for two days, very little, but fortunately four days after this arrived from Manila the rescue that allowed the Spaniards to continue to resist the siege. A few days after this event the Dutch and Ternatese rebels entrenched and besieged with artillery a fortress ‘nuestra’32 For the rescue of the garrison of this fort some soldiers were sent, including Juan de Origuey. They remained in defense of this fortress as long as the rebellion lasted, occasionally making forays in order to nourish plants and other wild food. The fort of Gomafo infact, being located on a high hill overlooking the city of the king of Tidore, was not easily supplied with food during a prolonged siege. Garzes informs us that during this period, many Spanish soldiers of the fort passed to the enemy, infact they could no longer tolerate hunger. Furthermore the enemies besieged every night a village of Tidorese friends of the Spaniards,33 located near the Spanish fort, to burn and destroy it and so the Spanish sent as garrison in the village a troop of infantry. In 1658, the enemy having left the trenches in which they besieged the Spanish fort, a troop of soldiers attacked the enemies, putting them to flee. The siege lasted almost a year and Origuey tells us that the Spaniards suffered hunger, having to eat trees and wild herbs, because of these hardships more than 100 soldiers went to the enemy.34 After these events the Spaniards remained at Tidore for a few more years, and as we shall see, dismantled some garrisons on the island already, starting in 1661-1662.

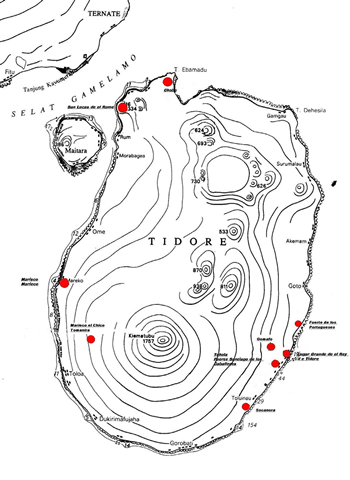

Now let us see in detail such forts the Spaniards occupied or built on the island of Tidore, in the period between 1606 and 1663. In Spanish documents, I have consulted, are mentioned about a dozen of names of forts, 35 or so garrisons on the island of Tidore, which, however, are not always easy to tell where they were actually located and during what period they were actually occupied by Spanish troops. Sometimes the same fort is called by different names at different times. The actual position of the forts is very difficult to define, according to data, I could gather, these are the most probable locations of the Spanish forts on the island of Tidore:

Chobo: (Cobo, extreme northern tip of the island)

Rume: (Rum, northwest of the island)

Marieco: (Marieko, west of the island, directly on the beach)

Tomañira (probably also Marieco el Chico): (just south of Marieko, was built on a high place, near Marieco (about half a league from Marieco (2960 m)).

Marieco el Chico (probably Tomañira): ‘media legua’ (2960 m) from Marieko.

Sokanora: (just south of Soa Siu, half a league (2960 m) south of the Lugar Grande, on a hill near the sea)

Tahula, Santiago de los Caballeros: (Soa Siu, located on a hill above the sea overlooking the Lugar Grande, south of it)

Baluarte del Principe: (Soa Siu, ‘fuerte de abajo’ located on the beach under Tahula)

Gomafo: (Soa Siu, fort of the King of Tidore, located on a hill in the interior facing to the sea)

Fuerte de los Portugueses: (just north of Soa Siu, located north of the Lugar Grande 3 shots of espingarda 750 m), or a quarter of a league (1480 m) or a big gun shot (1000 m))

LEGEND:

Gomafo: Fort of the King of Tidore

Marieco: (1614 and 1619) Dutch Fort

All other forts: Spanish forts

Continue: Defenses of the city of the King: Lugar Grande De El Rey (Soa Siu)

INDEX:

1 – The Spanish fortresses on the island of Tidore 1521-1663: introduction

3 – The Spanish expeditions to the Moluccas after the union with Portugal

4 – The Spanish forts of the island of Tidore 1606-1663

5 – The defenses of the city of the King of Tidore: Lugar Grande De El Rey (Soa Siu)

6 – Fuerte de los portugueses (Fortaleza dos Reis Magos)

7 – Tohula Fort, Santiago de los Caballeros

8 – Sokanora Fort

9 – Marieco Fort

10 – Tomanira Fort

11 – Chobo Fort

12 – Fort of Rume

13 – Puli Caballo Island

14 – Captains of Tidore (Fortress of Santiago de los Caballeros)

NOTES:

1 “Instrucción a Juan de Esquivel para conservación Terrenate, 02-11-1606” AGI: Patronato,47,R.17

In all probability the date November 2, 1606 is wrong, because Acuña died in June 1606, being a copy, it may have been a copyist’s error; the date May 2, 1606 seems to be plausible.

2 Argensola, Bartolomé Leonardo de “Conquista de las islas Malucas” (Madrid, 1609) (Madrid, 1992) 343

3 Colin-Pastells “Labor Evangelica de los obreros de la compañia de Jesus en las isla Filipinas” (Barcelona, 1902) vol. III 317 note n°1

4 “Carta di Geronimo de Silva a Felipe III, sobre el estado del Maluco, Terrenate, 13 de abril de 1612” in: Various authors “Correspondencia de Don Gerónimo de Silva con Felipe III, D. Juan de Silva, el Rey de Tidore y otros personajes desde abril de 1612 hasta febrero (abril) de 1617, sobre el estado de las islas Molucas” in: “Coleccion de documentos ineditos para la historia de España, tomo 52” (Madrid, 1868) 6

5 “Tanto de carta que el gobernador Gerónimo de Silva escribió al arzobispo de Manila, Terrenate, 28 de jullio de 1613” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 158-160

6 “Descripción de las islas de Terrenate,Tidore,y otras” AGI: Patronato,34,R.29

7 “Carta de D. Gerónimo de Silva al rey Felipe III, Ternate, 13 de abril de 1612” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 13

8 “Carta de don Geronimo de Silva a Felipe III, sobre el estado del Maluco. Terrenate, 13-04-1612” in Various authors “Correspondencia” 5-15

9 Matelief had arrived in Ternate with a fleet of eight vessels (six vessels and two ‘yachts’: Oranje, Mauritius, Erasmus, Kleine Zon, Pichon (?), one ‘yacht’ (Witte Leeuw ?), Enchuisa (Enkhuizen) (met in Ambon), Delft ( which had come from Banda)) with 531 men on board.

10 Tiele “De Europeers in den Maleischen archipel, 1606-1610” 70-72

“Fr. Luís Fernandes, superior to King Philip II of Portugal. Ternate, 27 de abril de 1608” Document n° 29 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 96

Prevost, Abate Antonio Francisco “Historia General de los viajes, ó nueva colección de todas las relaciones de los que se han hecho por Mar y Tierra… Tomo XIII: Viajes de los Holandeses a las Indias Orientales” (Madrid, 1773) 66-67

“Fr. Jerónimo Gomes to Fr. Jerónimo Gomes. Cochin, 25 de novembro de 1608” Document n° 35 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 119

de Jonge, “De Opkomst van het Nederlandsch gezag in Oost-Indië, 1595-1610”, (‘s-Gravenhage, 1862-1909) vol. III, 55.

11 “Informatie van den stant van de Molucques, door Jan Bruyn, 12 may 1609” in: “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azië , 1607-1612” vol. II, 303-304

de Booy “De derde reis van de VOC naar Oost-Indië onder het beleid van admiraal Paulus van Caerden uitgezeild in 1606” vol. I, 63-64

Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo VI (1608-1618) pp. xxxvi-xxxvii where is published the “Letter of Esquivel to the Audiencia, August 13, 1608” AGI 1-2-1/14, ramo 30

“Fr. Lorenzo Masonio to Fr. Claudio Acquaviva. Ternate, 20 de marzo 1609” Document n° 38 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 135, 144.

12 Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo VI (1608-1618) pp. xxxvi-xxxvii where is published the “Letter of Esquivel to the Audiencia, August 13, 1608” AGI 1-2-1/14, ramo 30

13 “Journael en de verhael”, in: “De reis van de vloot van Pieter Willemsz Verhoeff naar Azië, 1607-1612” vol. I, 276-281

“Informaciones Lucas de Vergara Gaviria, 1611” AGI: Filipinas,60,N.12

Tiele “De Europeers in den Maleischen archipel, 1606-1610” 102-103

14 “Fr. João Baptista to Fr. Claudio Acquaviva. Ternate, 2 de abril 1611” Document n° 53 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 192

Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 24*

15 “Fr. Jorge da Fonseca to Fr. Claudio Acquaviva. Ternate, 8 abril 1612” Document n° 59 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 217-218

16 “Fr. Jorge da Fonseca to Fr. Claudio Acquaviva. Ternate, 8 abril 1612” Document n° 59 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 224

17 “Carta di Geronimo de Silva a Felipe III, sobre el estado del Maluco, Terrenate, 13 de april de 1612” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 6

18 “Traslado de la carta que escribió el gobernador don Gerónimo de Silva al rey de Tidore, sobre la pérdida del puerto de Marieco, Terrenate, 10 de febrero de 1613” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 85

19 “Carta que escribió el sargento mayor don Fernando de Ayala […] al el señor don Gerónimo de Silva, Tidore, 16 de febrero de 1613” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 90-91

20 “Carta del Rey de Tidore a D. Gerónimo de Silva, Tidore, 9 July 1613” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 138

21 Kerr, Robert “A General History and Collection of Voyages and Travels, Vol. VIII.” Sec. XV. “Eighth Voyage of the English East India Company, in 1611, by Captain John Saris” Sec.5. “Further Observations respecting the Moluccas, and the Completion of the Voyage to Japan”

22 The orders to Gerónimo de Silva were clear, he had to move to Tidore with as many soldiers as possible, while still leaving a good garrison in Ternate. “Tanto de carta quel señor don Juan de Silva escribió á el señor don Geronimo de Silva en 20 de setiembre de 1614” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 255. In the “Correspondencia” by Geronimo de Silva, were written in Tidore the letters dated: May 5, 1612; December 12, 1614; May 12, 1615; July 13, 1615; August 19, 1615; March 8, 1616; April 1, 1616; April 17, 1616; June 17, 1616; June 25, 1616; August 8, 1616; August 20, 1616 and March 12, 1617.

23 Rios Coronel, Hernando de los “Memorial y relacion…” 1621, Madrid, Spain, in: Blair, E. H. e Robertson, J. A. “The Philippine Islands, 1493-1898” vol. 19 (1620-1621), 214 where is an excerpt of the letter of Gerónimo de Silva to the governor D. Juan de Silva, July 29, 1616.

24 “Lettera di Gerónimo de Silva a D. Juan de Silva, Tidore, 8 agosto 1616” in: Various authors “Correspondencia” 387-388

25 “Carta de Lucas de Vergara Gaviria al Rey defensa Maluco. Terrenate, 31 maggio 1619” AGI: Patronato, 47, R. 37

Pastells “Historia general de Filipinas” tomo VI (1608-1618) pp. clxvii-clxviii, Here are some passages of the same letter of Vergara.

26 “Catalogue of the Philippine Jesuits for the Holy Congregation de Propaganda Fide. Manila, 20 Iunii 1662” Document n° 196 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 615.

“Catalogue of the Jesuit missionaries in the Philippines for the Holy Congregation de Propaganda Fide. Manila, 31 Julii 1663” Document n° 201 in: Jacobs, “Documenta Malucensia III, 1606-1682” 624.

27 “Carta de Corcuera sobre socorro de Terrenate y Cachil Naro. Carta de Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, gobernador de Filipinas, dando cuenta del envío del socorro a Terrenate; encuentro que tuvieron con un galeón enemigo y regreso del gobernador de Terrenate, Pedro de Heredia. Por triplicado. (Cat. 16196)

Acompaña: Orden e instrucción que los generales Pedro [Muñoz de Carmona y] Mendiola, gobernador de Terrenate y Jerónimo Somonte, capitán general de la armada real deben de guardar en razón de la restitución del rey Cachil Naro a su reino. Manila, 5 de julio de 1636. Con duplicado. (Cat. 16199). [c] 02-07-1636. Manila” AGI: Filipinas,8,R.3,N.72

28 “Confirmación de encomienda de Bacnotan, etc Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Bacnotan y Binmaley en Pangasinan a Pedro Muñoz de [Carmona y] Mendiola. Resuelto. [f] 23-05-1647” AGI: Filipinas,49,N.66 Block 1 sheets 2-7

“Informaciones: Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola. Informaciones de oficio y parte: Pedro Muñoz de Carmona y Mendiola, general, vecino de Manila, casado con María de Valmaseda, única descendiente de Martín de Esquivel, sargento, Juan de Esquivel, maestre de Campo y Juan Ezquerra, general. Información con parecer. Duplicado. Tres minutas de pareceres. [f] 1649” AGI: Filipinas,61,N.26 Block 1 sheets 3, 5, 11-13, 28-29, 38, 40, 50-52, 64-66, 76-79, 152-153, 161-191, 213-215; Block 2 sheet 3; Block 4 sheets 2-3; Block 5 sheets 2-3; Block 6 sheet 2; Block 8 sheets 9-11

29 “Confirmación de encomienda de Mambusao. Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Mambusao en Panay a Sebastián de Villarreal. Resuelto. [f] 19-05-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.11

30 “Confirmación de encomienda de Baratao. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Baratao en Pangasinan a Alonso Lozano. Resuelto. [f] 16-06-1676” AGI: Filipinas,54,N.12

31 “Confirmación de encomienda de Majayjay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Majayjay y Santa Cruz en La Laguna de Bay a Juan Rodríguez de Origuey. Resuelto[f]. 08-06-1695” AGI: Filipinas,58,N.3

32 This was the fort of Gomafo, as is to be seen from a later document, the memorial of Juan de Origuey: shortly after the enemy entrenched himself at a musket shot from the fortress ‘Domafo‘ (Gomafo) that was located in a very strategic place ‘por ser eminente alas de mas‘ and the fortress in question being in grave danger, the Spaniards sent some soldiers, including Juan de Origuey to reinforce the defenders of the fort, Origuey was fighting in defense of the fort day and night. Origuey did during this siege several sorties against enemy defenses and was trying to get food and also defended the village of ‘mori‘, faithful to the Spaniards; ‘defendio el pueblo de los moros de nuestra parcialidad‘, located below the fort until the enemy was forced to retire. “Memorial of the ensign Juan de Origuey” (Manila, 20 September 1673) (sheets 18-20), in: “Confirmación de encomienda de Batangas, Expediente de confirmación de la encomienda de Batangas en Balayan a Lorenzo de Zuleta, Resuelto, [f] 03-04-1677“, AGI: Filipinas, 54, N.14.

33 This was the city of the king of Tidore, located on the site of Soa Siu.

34 “Confirmación de encomienda de Majayjay, etc. Expediente de confirmación de las encomiendas de Majayjay y Santa Cruz en la Laguna de Bay a Juan Rodríguez de Origuey. Resuelto[f]. 08-06-1695” AGI: Filipinas,58,N.3

35 For example, van de Wall lists only 4 forts on the island of Tidore: Vesting Tahoela (Soa-Sioe), Vesting Tsjobbe (Soa-Sioe), Fort Roemi (Roem), Fort Marieko (Marieko).

van de Wall, V. I. “De Nederlandsche oudheden in de Molukken” (‘s-Gravenhage, 1928) 267-269, 291-292.