This post is also available in:

![]() Italiano

Italiano ![]() Português

Português

Written by Marco Ramerini. English text revision by Dietrich Köster.

Continued from: Introduction

2.0 THE FIRST CONTACTS WITH THE PORTUGUESE

A first interest of the Portuguese with regard to Trincomalee has been in the first years of the 1540s. All had begun, when the king of Kandy, Jayavira, on the advice of Nuno Alvarez Pereira 1, asked the Portuguese governor Martim Afonso de Sousa to open a ‘feitoria’2 with a factor in Trincomalee and to send Portuguese soldiers to Kandy. The king of Kandy on that occasion promised also to pay a tribute to the king of Portugal. It’s obvious that the main aim of the king of Kandy, beyond establishing direct trade relations with the Portuguese, was to receive military aid against the kingdoms of Kotte and Sitavaka, which laid claim to the reign of Kandy.

In February 1543 the demands of Jayavira seemed on the point of being fulfilled. Actually for this purpose a Portuguese expedition started from Negapatnam, guided by Amaro Mendez 3 and Miguel Ferreira,4 and arrived in the bay of Trincomalee. About 60-80 Portuguese were initially a part of this expedition. The king learnt about the arrival of the Portuguese and immediately sent a contingent of 2,000 men to Trincomalee. Together with the Portuguese Nuno Alvarez Pereira these men had to join the Portuguese in Trincomalee. They were supposed to be of assistance and support for the construction of the small trading base and later to be partly transferred to Kandy. But the expedition was a failure, because there were numerous defections among the Portuguese, caused by the lack of provisions, the hostility of the local head and by the incomprehension between the two parts.5

According to what Queyroz said, also Saint Francisco Xavier visited Trincomalee in 1543-44 , converting some inhabitants and being confronted in religious topics with some local religious heads.6 A letter written by Nuno Alvarez Pereira in 1545 did not mention clearly specified heads of Trincomalee (Trycanamalle) that 3,000 persons wanted to be converted together to the Christian faith.7 This demand for conversion could have been the consequence of the visit of the saint.

Notwithstanding the first failure, Jayavira still insistently demanded the aid of the Portuguese in 1545. This time the King offered to pay the tribute to the King of Portugal and the permission to build a small trading post in Trincomalee and also the payment of the wages for the factor and an employee of the trading farm. Besides he also offered to pay the wages for 20 more men, who had to reside in his capital city and finally also promised his conversion and that of his family to Catholicism.8 Like an answer to these demands in March 1546 a new expedition was sent by the governor of Portuguese India to the aid of the Kandyan kingdom.9 To the precise question of the captain of the expedition, André de Sousa, which route to follow to reach Kandy, the king Jayavira ordered that they should proceed by the way of Trincomalee. With a troop of Singhalese Nuno Alvarez Pereira was sent by the king to Trincomalee to help the Portuguese contingent in their transfer to Kandy. But when the Kandyan troops arrived in Trincomalee, they saw that once again the Portuguese expedition had disappeared, and of the supposed 150 soldiers only 13 or 14 Portuguese had stayed behind. The reason for this was that the soldiers, who had arrived in Trincomalee, had been strongly attacked by the inhabitants of the region and were forced to withdraw to Negapattam. A part of the Portuguese soldiers reached Kandy via Yala. In all approximately 50 soldiers arrived in Kandy.10 The envoy of the king of Kandy, Nuno Alvarez Pereira, was then abandoned by nearly all his men, afraid of an eventual attack by the inhabitants of the district of Trincomalee. But fortunately the feared attack didn’t materialize.11 It is understood by these events that the territory of Trincomalee, even if nominally subject to the king of Kandy, was not a really sure one for the Kandyans. But in spite of this Jayavira thought that the road, which started for Trincomalee was the safer one to reach Kandy.12 Miguel Fernandes13 indicates in one of his letters the reason of the behaviour of the inhabitants of Trincomalee. According to his writings the reason of those reactions seemed to be rumours of the conversion to Christianity of Jayavira.14

Still in 1546 some ambassadors of the ‘king’ of Trincomalee were present, through them he insistently asked the Portuguese to become Christian.15 A letter (dated 16 March 1547) written by João de Vila de Conde de Castro introduces us into a new request by the king of Kandy concerning the construction of a ‘feitoria’ in the port of Trincomalee. This time the king of Kandy had also promised to appoint Nuno Alvarez Pereira for this place as a factor.16 Fulfilling this request in 1547, a new contingent of Portuguese reached the eastern coast. They were about 100 men under the command of António Moniz Barreto. Although this time the disembarkation point had initially been fixed in Trincomalee, the Portuguese disembarked in Batticaloa and arrived in Kandy this way. However, this expedition will also end in a failure.17

In the last months of the year 1551 the prince of Trincomalee, a boy hardly seven or eight years old, was christened by father Anrriques. The reason of his conversion was to be found in a power struggle between two factions. One of these, guided by a leader, namely the uncle of the young prince, was thinking to benefit from the aid of the Portuguese, thus deciding to transport the young prince to the coast of Pescaria 18, where the Portuguese Jesuits resided. Here all the party insistently asked to be converted to Christianity. In this way the prince, his uncle and 30-40 of his followers became Christians. An expedition to put the prince in power in his province was also organized. About 1,000 Christians and some Portuguese participated in this campaign, but owing to the state of rebellion of the region the expedition did not obtain the hoped results and after two months it was decided not to put in danger the life of the prince and to abandon the enterprise. The young prince, who had been christened as D. Afonso (Afonço), was sent to Goa where he was introduced to the Viceroy. In Goa he was educated in the college of São Paulo and entrusted to the spiritual cures of father António Gomez.19 Subsequently in 1560, when the Portuguese tried to conquer Jaffna, the prince of Trincomalee participated in the expedition. The Viceroy D. Constantino de Bragança thought that once conquered Jaffna, this circumstance would bring him back Trincomalee, where he would be able to resume his reign and helped the Portuguese in the conversion of his people. But the expedition did not have the hoped results and the prince never reached Trincomalee. He instead returned to Goa.20 During his life in Goa he also conducted a correspondence with King D. Sebastião of Portugal.21 In 1568 he participated as a voluntary in the siege of Mangalore, where he was killed.22

A few other people mention Trincomalee in the following years:

In 1555 there was a request for missionaries by the Christians of Trincomalee to realize the christianization as far as Punnaikayala on the coast of Pescaria. But the insufficient number of clergymen prevented every mission.23 In 1560, the king of Jaffna, panic-stricken during the assault of his capital, carried out by the Viceroy de Bragança, escaped together with the royal family, sheltered in the territory of the vanniyar of Trincomalee, from the Portuguese .24 In 1569 two Portuguese ships arrived in the port of Trincomalee to take aboard the princess of Kandy, daughter of Karaliyadde (Javira Astana), to become the spouse of King Dom João.25

As we have seen, although the timid attempts by the Portuguese to install a ‘feitoria’ in the years between 1543 and 1547 meant that Trincomalee and the eastern coast remained for the entire 16th century free from Portuguese settlements. In the meantime they had extended their control over the south – western coastal area of the island. Practically till the end of the 16th century the Portuguese had the control over the territories, which once belonged to the reigns of Kotte and Sitawaka and moreover controlled the island of Mannar. However, toward the last decades of the century the influence of the Portuguese power began to be felt on the eastern coast. Starting from the years around 1570, the Portuguese began to collect tributes from the vanniyar of Trincomalee and also from that of Batticaloa.26 A protection tax was also imposed on the Hindu temple of Konesar (Koneswaram) in Trincomalee. Then the Portuguese collected taxes on some goods the reign of Kandy exported through the two main ports of Trincomalee and Batticaloa.27

In 1582 at the time of the conquest of the reign of Kandy by the troops of Sitavaka, the king of Kandy Karalliyadde Bandara (Dom João) together with some Portuguese who had helped him, took shelter in Trincomalee. This happened immediately after the defeat of his troops fighting against those of the reign of Sitavaka. It was exactly in Trincomalee that the king died of an epidemic of smallpox. Among the Portuguese, who followed the king Karalliyadde to Trincomalee was also the Franciscan friar André de Sousa.28 The king of Ceylon D. João Parea Pandar, Dharmapala, mentioned in a certificate on the work of the Franciscans in the reign of Kotte also the name of the Franciscan friar André de Sousa, who had sacrificed his life in Trincomalee. A mention of the same friar was also made by Trindade .29

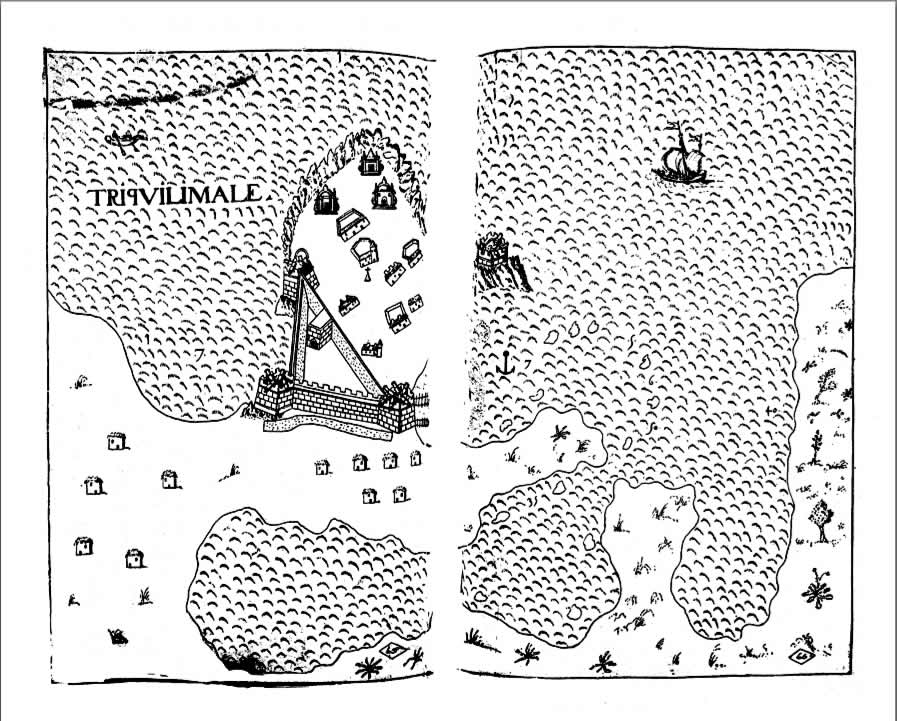

In 1602 the region lying between Jaffna, Trincomalee and Batticaloa was assigned to the spiritual cures of the Jesuits. They had the permission to erect churches and to convert the inhabitants.30 In that very year the first Portuguese order for the construction of a fort in Trincomalee occurred.31 This order must be surely a first Portuguese reaction to the arrival of a Dutch expedition and to the subsequent first contact between the Dutch and the king of Kandy, which had taken place in the region of Batticaloa in 1602. Another motivation was the fact that during the periods of war with the Portuguese, Trincomalee was used as one of the ports through which the king of Kandy received aids and troops from the Nayak of Madura and the king of Meliapor.32

In the years around 1605 and 1609 D. Francisco de Menezes twice reached Trincomalee during military expeditions against the king of Kandy.33 A more detailed description of one of these expeditions is reported in the annual relation of the Jesuits of 1606. In fact here you find the description of a punitive expedition, which occurred in 1606 to fight a rebellion. The expedition was composed of a squadron of Portuguese soldiers and 4,000-5,000 Singhalese lascarins. in its way it also reached Trincomalee, being the place of the capture of about 200 men, women and children, who on the order of Simão Correia (a Singhalese captain) were beaten to death and for ‘compassion’ all were christened before being killed.34

A letter of the Jesuit frei Barradas, written from Cochin in November 1613, narrates the following Portuguese expedition to Trincomalee, which happened in the year 1612. The expedition was guided by D. Hierónymo de Azevedo. He crossed the Kandyans mountains, where underway were discovered two large tanks. “…our people came across two remarkable tanks. They were four legues in length, skillfully hemmed around by dug out mountains and by a wall, a piece of wonderful workmanship that one would expect from the Romans rather than the Chingalas”. After great difficulties due to torrential rains the Portuguese arrived in Trincomalee, and here de Azevedo “was keen on building a fort”. For this purpose he called in aid the king of Jaffna, but not seeing him to arrive he abandoned the enterprise and he marched towards Jaffna.35 A short description of this enterprise in Trincomalee was made also by Bocarro. He factually narrates that de Azevedo was waging a war in parts of Trincomalee, when he received the news that he had been proclaimed Viceroy.36 Another text narrates us instead the plans that de Azevedo cared for the fortification of Trincomalee and Batticaloa, and leaving Ceylon in November 1612 to go to Goa to assume the assignment of Viceroy. He planned to send in March of the following year ‘seis navios’ with the necessary materials for the construction of the fortresses of Trincomalee and Batticaloa and even planned to send two ships to patrol the coast of Galle and ordering these ships to stay the next winter in Trincomalee to assist in the construction of the fortress.37 According to de Azevedo one of the better ways to weaken Kandy was exactly to block the commerce of the kingdom, exerted from the ports of Batticaloa, Trincomalee, Rio de Água Doce and Jaffna. But for the moment (1614) he judged the Portuguese not to be able to occupy all these ports.38

Subsequently in the peace treaty between the king of Kandy and the Portuguese, signed in August 1617, were also defined the frontiers between the two territories, establishinged also the borders along the eastern coast, where the two main ports, namely Kottiyar/Trincomalee and Batticaloa, remained under the control of the kingdom of Kandy. In the treaty it was factually indicated that the frontier of the territories under the authority of the king of Kandy reached as far as the ports of Kottiyar, Batticaloa and Panama.39

In the year 1619 all the territory of the kingdom of Jaffna, including Trincomalee and Batticaloa, was assigned to the spiritual cures of the Franciscans. This decision was taken by the bishop of Cochin, fray Dom Sebastião de S. Pedro.40 Later another decree of the same bishop of Cochin, dated 11 November 1622, based on a earlier decree of 1602, entrusted anew the spiritual cure in the districts of Jaffna, Trincomalee and Batticaloa to the Jesuits, giving them the possibility to build churches, to teach the sacraments and to convert the souls.41 And in fact the Jesuits were to follow the Portuguese soldiers to Trincomalee and Batticaloa, when they occupied the two localities.

To be continued by: The arrival of the Danes, the Dutch and the construction of the Portuguese Fort

NOTES:

1 Nuno Alverez Pereira was a Portuguese soldier who reached Kandy in July 1542 and soon became a councillor and secretary of King Jayavira.

2 A fortified factory.

3 Amaro Mendes had been appointed factor of the feitoria.

4 Miguel Ferreira was the Portuguese captain of the Coromandel coast. For the life of this important personality confer the article written by J. M. Flores “Um Homem que tem muito crédito naquelas partes: Miguel Ferreira, os alevantados do Coromandel e o Estado da Índia”, in: “Mare Liberum”, n° 5/1993, pp. 21-32.

5 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, pp. 80-81.

6 Queyroz “The temporal and spiritual…”, vol. I, pp. 236-237.

7 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 62.

8 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period” vol. I, pp. 71-72.

The tribute promised from the king of Kandy was: “fifteen elephants with tusks and three hundred oars of beech wood for the galleys.” Vedi: Perniola, V. “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, pp. 86-87.

9 The reign of Kandy had been attacked since November 1545 by the forces of the reign of Sitawaka, thus needing support urgently

10 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 162, 177.

11 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, pp. 160-161.

12 In order to reach Kandy the road, which started in Batticaloa, was also often used.

13 Miguel Fernandes was a Portuguese “casado” (married soldier) from Kotte.

14 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 177.

Jayavira was secretly christened by friar Francisco di Monteprandone on 9 March 1546.

15 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 154.

16 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 216.

17 For the details of this expedition see: O. M. da Silva “Vikrama Bahu of Kandy. The Portuguese and the Franciscans, 1542-1551”, pp. 63-76.

18 The Indian coast around Tuticorin.

19 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, pp. 286-288.

20 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 372, 374, 382.

21 See the letter of answer of King Sebastião dated 7 March 1567 and published in: Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. II, p. 23.

22 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 382 n. 1 and vol. II, p. 23 n. 1.

23 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. I, p. 346.

24 “History of Sri Lanka”, vol. II, p. 110.

25 Queyroz “The temporal and spiritual…”, vol. II, pp. 423.

26 “History of Sri Lanka”, vol. II, p. 92.

27 “History of Sri Lanka”, vol. II, p. 112.

28 F. F. Lopes “A evangelização de Ceilão desde 1552 a 1602”, in: “Studia” n° 20-22/1967, pp. 30-31; “History of Sri Lanka”, vol. II, p. 96.

29 The certificate is dated 1 December 1594. Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. II, p. 137; Trindade “Conquista espiritual do Oriente”, vol. III, p. 56, 68.

30 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. II, p. 266.

31 Silva, Ch. R. de “The Portuguese in Ceylon, 1617-1638”, p. 59 nota n° 149.

32 Abeyasinghe “Portuguese rule in Ceylon, 1594-1612”, p. 36.

33 Queyroz “The temporal and spiritual…”, vol. II, p. 611.

34 Perniola “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. II, p. 256.

35 Perniola, V. “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, Vol. II, p. 366.

36 Bocarro “Década 13 da história da Índia ”, vol. I, p. 11.

37 “Relación del estado en que quedavam las cosas de la India, sacada de las cartas, que escrivio el virrey Dom Hieronymo de Azevedo…”, published in: “Documentação Ultramarina Portuguesa”, vol. I, p. 73 and vol. II, p. 157.

38 Bocarro “Década 13 da história da Índia ”, vol. I, p. 277.

39 “History of Sri Lanka”, vol. II, p. 154 and also Silva, Ch. R. de “The Portuguese in Ceylon, 1617-1638”, p. 59.

40 Perniola, V. “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. II, p. 458.

41 Perniola, V. “The Catholic church in Sri Lanka. The Portuguese period”, vol. III, p. 51.